Hofu Cultural Trip

In September, I was one of a diverse group of around 20 international residents on a cultural tour of Hofu in neighboring Yamaguchi Prefecture. I have to admit that, until this trip, I had been rather dismissive of Hofu. I had taken part in the annual marathon race here not long after I first moved to Hiroshima and, although fast, the course didn’t suggest that this was a city worthy of further exploration. With this in mind, assembling early on a rainy morning I wasn’t quite sure what to expect. Our guide for the day. however, was full of energy, and the group friendly, so off we went. Our first stop in Hofu was Eiunsō, an official residence of the Mōri Clan built in 1654. Our guide gave us an abbreviated history of the Mōri as we made our way along the Sanyo Expressway. During the medieval sengoku warring states period, notably under the leadership of Motonari Mōri (of 3 arrows fame), the clan expanded its power from a small area in the north of what is now Hiroshima prefecture, to encompass the whole of western Honshu. At the height of their power the Mōri moved their base to the coastal river delta that would become the city of Hiroshima. In 1600, however, only a few short years after the construction of Hiroshima Castle, the Mōri picked the wrong side in the epoch-making Battle of Sekigahara and found their lands greatly reduced and the clan was forced west to Hagi on the Japan Sea coast. The Mōri’s misfortune was Hofu’s gain. Clan leaders were required by order of the shogun to make regular trips to Edo. The small port of Mitajiri, just south of where Hofu railway station is now located, was at the end of the overland route from Hagi and where the clan leaders and their large entourages would board and disembark ships to and from the capital. As a result Hofu is home to some beautiful and significant heritage sites.

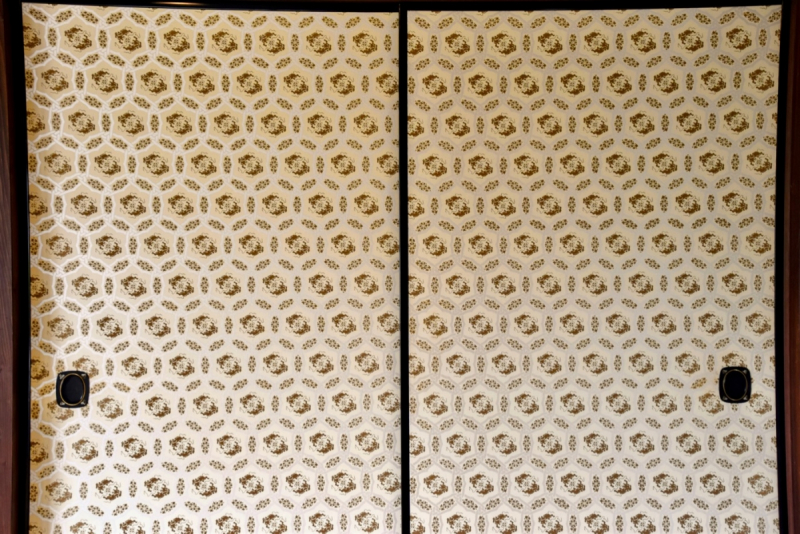

Eiunsō is one of these. Formerly known as the Mitajiri Ochaya (Mitajiri Teahouse), clan leaders and their guests would stay here on their journeys to and from Edo, and when touring or visiting the domain. As the building undergone several large scale renovations since it was first built in 1654, design features from different eras can be seen throughout. Before we explored the building, however, it was calligraphy experience time. *Unfortunately, this isn’t a regular event offered to visitors, but we hope it will be in the future. We were ushered into a large tatami mat room and took our places at low Japanese tables on which everything we would need to create some Japanese calligraphy was neatly arranged. Calligraphy teacher, artist and musician, Masumi Kuniyoshi, was to be our guide. She wasted no time in getting everyone started, instructing us to start prepare the ink we would be using. Rather than squeezing from a bottle, we were to make our own ink in the traditional way. We were encouraged to grind our ink stick on the stone slowly and carefully. It took some time to produce the ink and resisting the urge to go too fast was an exercise in patience. We were asked to pick a word to be written either in phonetic hiragana syllables or Chinese kanji characters and given plenty of paper on which to practice. Kuniyoshi-sensei kept an eye on our progress, giving tips and encouragement along the way. It was refreshing that she stressed that there was no real “correct” way of writing calligraphy and urged us all to take an artistic approach to interpreting the characters we had chosen. Sensei would use orange ink to daub corrections on our attempts, or sometimes, in the case of a particularly well executed example, a swirling circle, or even a large flower. After plenty of practice it was time to commit our calligraphy to the final decorative piece of framed paper and to add our own personal Japanese signature for that stamp of authenticity. As our calligraphy session came to an end, the head curator of Eiunsō gave us a brief history of the building. He pointed features to take particular note of, such as ornamental kugi-kakushi nailhead covers, elaborate latticed transoms and a somewhat rare hiwadabuki roof covered in hinoki cypress bark shingles. We were then given free reign to explore the building and the attached tea house in the garden. We had great fun trying out the tiny door that guests had to crawl through to enter the tiny Kagetsurō tea house; the door to enforce a degree of humility on the samurai who came to take tea, and the small dimensions to prevent the brandishing of swords! We were also shown a narrow hidden alcove in which spies could conceal themselves to ensure that guests were not plotting while sipping their tea. We were scheduled to enjoy our own tea ceremony at another location later in the afternoon, but first it was time for lunch. We took the bus the short distance from Eiunsō to Hofu Tenmangu Shrine, where we were greeted by friendly souvenir shop vendors, surprised, but certainly not perturbed, by this large group of non-Japanese visitors, as they tried their best to describe their wares in a mixture of English and Japanese. Lunch was in the Ume Terrace at the entrance to the approach to the shrine which is Hofu’s main attraction. Everyone seemed to enjoy the mixed plate lunch. The restaurant’s head chef went to considerable effort to accommodate the 4 vegetarians in our group with what turned out to be a very tasty meat-free option. Vegetarians considering eating here should, however, plan on booking ahead and be aware that the miso soup that came with our lunch plate, while free of additives, did contain fish and seafood stock. Energy restored, we took a look at Ume Terrace’s souvenir shop with lots of local products such as a kind of sweet made from mochi rice flour called uirō. There were also some more surprising items; limited edition Coca Cola bottles commemorating the 150th anniversary of the Meiji Restoration in which samurai from this region played a major role and a wide range of Japanese Self Defence Force goods. Leaving the souvenir store behind we next moved on to Hofu’s most famous attraction; Hofu Tenmangū Shrine. Tenmangu Shrines are dedicated to the scholar-poet Sugawara No Michizane, posthumously known as Tenjin. There are around 12,000 Tenmangū Shrines around Japan, but Hofu Tenmangū is considered to one of the three most important, the other two being Daizaifu Tenmangū in Fukuoka and Kitano-Tenmangū in Kyoto. Said to have been built in 904, it is also the oldest. As Tenjin is the ‘God of Wisdom’, it makes sense that Tenmangū Shrines are the top choice for students looking for some divine help on their road to academic success, and hundreds of wooden ema plaques on which prayers for high scores in exams are written can be found at Hofu Tenmangū. The main shrine building, at the top of an impressive (and steep) stone staircase is beautifully colored and the unfinished Shunpūrō pagoda makes for a good viewing point over Hofu and out to the port through which the Mōri samurai once passed. Just off the side of the steps up to Hofu Tenmangū is the Hōshōan garden and tea house. It is nothing short of idyllic and, although the shrine gets all the attention, Hōshōan is a must see. For just ¥500 you can not only enjoy the gorgeous Japanese garden and the well maintained tea house, but you can take tea too. Miko shrine maidens dressed in striking red and white robes serve guests a cup of matcha tea with a Japanese sweet cake. Despite the location and impeccable service, the atmosphere is relaxed, so you don’t have to feel nervous about knowing little to nothing about tea ceremony. As a large group we were served in the spacious room with large windows looking out onto the garden. If you are in a small group, you may be served tea in a more intimate room, to get to which you have to cross a lovely little covered bridge which crossed the pond filled with colorful koi carp. Don’t forget to go check out the tea room on the upper floor and the 800 year old sacred tree just inside the garden’s entrance too. Hōshōan is beautiful at any time of the year, but it simply stunning during the autumn when the maple leaves turn deep red. It was tough to tear ourselves away from Hōshōan, but we had one last stop on our cultural tour of Hofu; the Former Main Residence of the Mōri Clan. This residence was built after the overthrow of the Tokugawa family who had forced the Mōri to Hagi after they took control of the shogunate over 250 years earlier. It is a huge and grand building, full of extremely fine woodwork and set before a huge Japanese garden which surrounds a large pond. Exploring the residence is an architecture buff’s dream and the attached museum has a selection of the 20,000 fascinating artifacts in its collection on display. Unfortunately, there is little English explanation in the museum, but quirky items such as a delicate blow up globe and the stunning Landscapes of the Four Seasons, a scroll by the 15th century artist Sesshū, are easy to appreciate. Before heading back to Hiroshima on the bus, there was just time to enjoy a drink and some dessert in dainty cafe and gallery Mai, which in itself was like stepping back in time. Be warned, however, the decor and menu may be conservative, but the bathroom, which you can click here for more info, is not for the shy! The cultural charms of Hofu surprised not only me, but other members of our group and on the 2 hour bus ride back to Hiroshima many of us were planning a return visit during the autumn colors in November. GetHiroshima was invited as a guest on this monitor tour organized by Hofu City and JTB Yamaguchi on September 15, 2018. See more pics from the tour on Instagram.