Tulip Needles, maker of one of Hiroshima’s most surprising exports

A kamikaze pilot, saved by a stroke of fate, returns to Hiroshima and revives a legacy of samurai industry that continues to endure today.

The overwhelming majority of Japan’s needles are made in Hiroshima. A charred clump of needles fused together by the A-bomb blast is on display in the city’s Peace Memorial Museum, while a short distance away, a monument dedicated to needles stands in a city park –– an indicator of the importance of needle manufacture in Hiroshima that long predates the bombing.

From samurai side-job to worldwide exports

Colored Picture Scroll of Sumiya Iron Mine from the private collection of Masahiro Kake

※Important Cultural Property of Hiroshima Prefecture

Needle manufacture in Hiroshima goes back over 300 years to when the local lord invited a Nagasaki craftsman to teach needle making skills (learned from state engineers visiting from China) to low ranking samurai as a way to supplement their income. The samurai fashioned needles from iron sent by river from tatara forges in the nearby Chugoku Mountains which were rich in iron sand. These needles were then shipped to wholesalers in other parts of Japan by ship.

In the 1880s, cheaper needles from Britain and Germany started to flood the market. Improvements made to German-made machines by a Hiroshima-based company, however, led to an increase in production and distribution of Hiroshima needles. However, a Hiroshima-based company succeeded in improving German-made machines. The disruption of needle exports from England and Germany during World War I proved to be an opportunity for Japan to which China turned for its needle supply. A growing number of needle makers in Hiroshima began to produce needles for export. Thanks to steady improvements over the following years, “Hiroshima Needles” became known for their quality and reliability overseas as well as at home.

A soldier’s homecoming and a mother’s words

Although the number of needle factories in Hiroshima grew to as many as 200 during World War I, the number dropped to around 100 after the war, all of which were obliterated by the A-bomb blast on August 6, 1945.

It was this sight of devastation that greeted a young man returning from war several months later. Atsushi Harada had dropped out of school two years earlier at the age of 16 to enlist in the military. He had been preparing to embark on a suicide mission as part of a Special Attack Unit based in Qingdao in China, when, in a stroke of fate, his unit’s “kamikaze” planes were destroyed in an air raid.

Atsushi managed to find his family and, the following year, they moved to the Kusunoki district, about 2.5km from the A-bomb hypocenter, which had been the center of Hiroshima’s pre-war needle production. Here, Atsushi’s father set up Harada Ironworks, and, taking advantage of his father’s engineering experience, started repairing machinery for the needle makers returning after the war.

As Japan recovered from the war, orders for needles from overseas grew. Another boost at home came from women’s magazines, which were growing in popularity and full of the latest fashions and instructions as to how to make them at home. Sensing another opportunity, Atsushi’s mother suggested that, as he was already making machines that others used to manufacture needles, he should grab a slice of this growing market by making his own. Thus, Harada Ironworks transformed into Harada Needle Manufacture.

A brand is born

Harada Needle Manufacture’s first foray into manufacturing wasn’t actually with sewing needles, but fishing hooks. Fishing hooks start life as steel wire, the same raw material from which needles of all kinds are made and require similar processing. Thanks to the support of other factories which shared how to transfer these skills with them, the company finally started producing sewing needles in 1950.

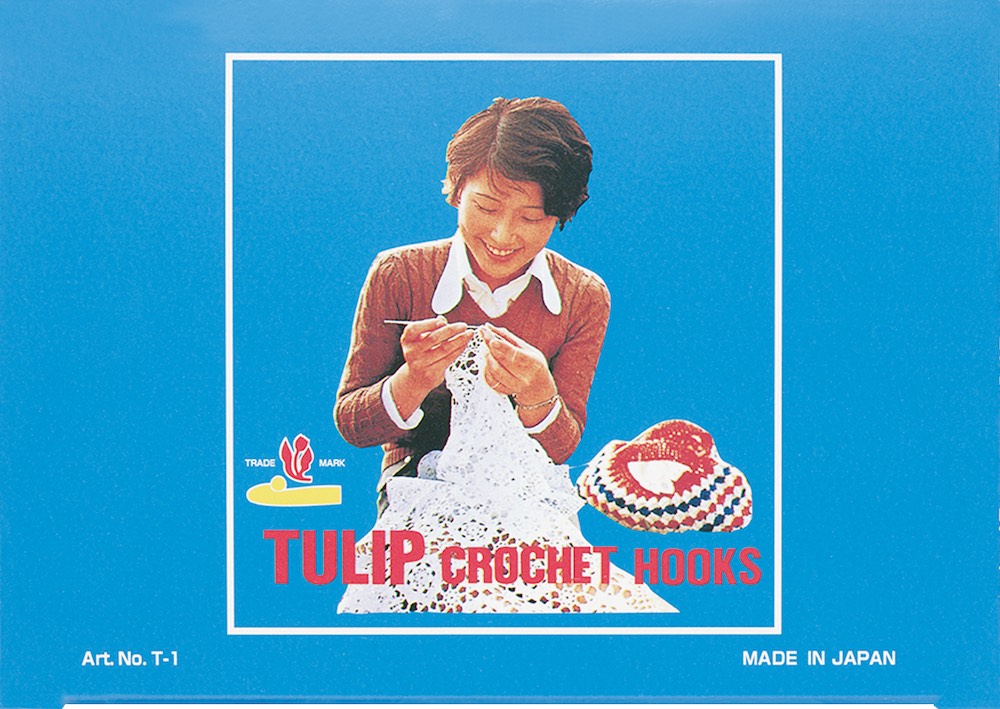

After a request to add lace crochet hooks to their line, Harada Needle Manufacture, the first company in Hiroshima to make crochet hooks, was able to ride a crochet boom that followed the 1953 hit film Kimi no na wa (What’s Your Name?), fans of which were eager to emulate the distinctive shawl worn by the lead actress. Orders for crochet hooks started to come in from Turkey, a country which had a long tradition of lacemaking, and which became an important export market.

When Harada Needle Manufacture was fulfilling wholesale OEM contracts, however, they found themselves being forced to sell at cheaper and cheaper prices. Realizing that this wasn’t sustainable, Atsushi saw that it was time to build his own brand.

Thus, in 1955, Harada Needle Manufacture made a considerable investment in purchasing the Turkish brand name, Tulip, introduced to him by a Kobe based trading company. As well as being cheerful and memorable, the brand helped secure a stable position in the Turkish market (the tulip is Turkey’s national flower) which would safeguard against fluctuations in their home market. Harada Needle Manufactures would change its name to Tulip in 1970.

Growing up with Tulip

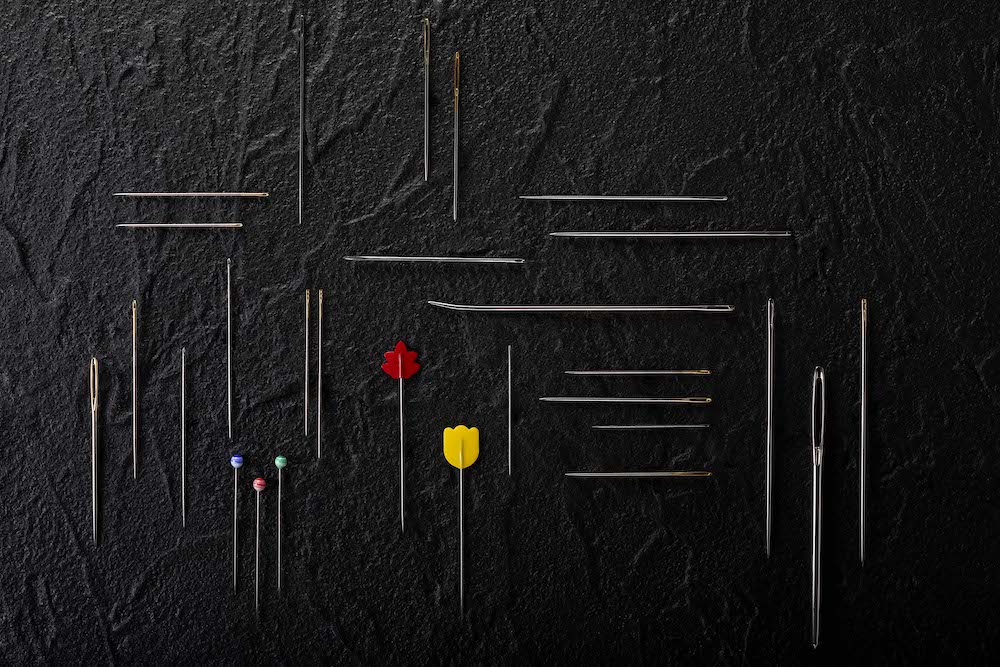

In 1968, Harada Needle Manufacture developed cellulose-head pins for schools. The flower-shaped, cellulose tabs not only made the needles easier to handle and less likely to roll off desks, but as the name of their owner could be written on them in pencil, they were easy to identify if they got mixed with those of other students. These bright and cheerful pins are still used in elementary school home economics classes today.

Relocation to Kake

Although Tulip’s head office is still in Kusunoki in Hiroshima City, in 1965, production was moved 50km up the river to the town of Kake (now Akiota Town) – from where the iron Hiroshima’s samurai turned into needles was first shipped 300 years before.

Tetsuo Yokokawa has been with the company longer than anyone else, and he recalls the early years after the move. “We never used to have heating or air conditioning – some parts of the factory even lacked walls.” He talks about tough times, but, looking back on a career of more than 60 years, his gratitude and love for the company is clear.

Soon after the move, founder Atsushi gave his son (current president Kotaro Harada) the task of bringing the new factory up to JIS (Japanese Industrial Standards) standards in order to improve quality and strengthen their quality control. Kotaro threw himself into the task and attained the all important certification 4 years later, setting the stage for a new period of growth.

Where machinery and craftsmanship meet

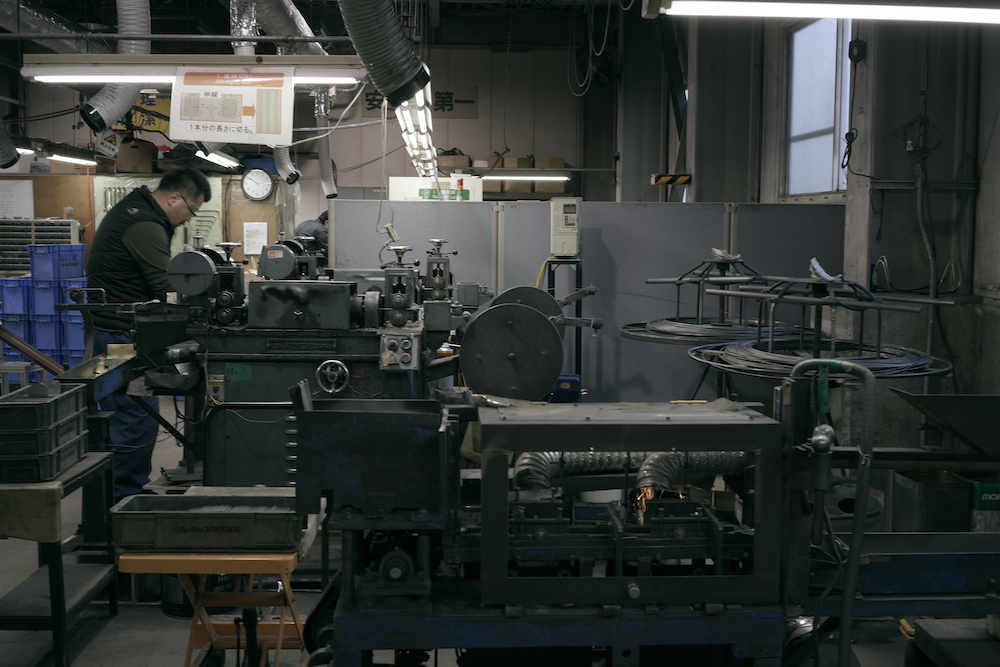

Tulip’s Kake factory produces around 10,000 needles of various kinds every day. Each undergoes around 30 different processes in its transformation from steel wire. Known for being particularly easy to thread, their exceptionally sharp points and a polishing process that minimizes friction, needleworkers rave about what a joy Tulip needles are to use.

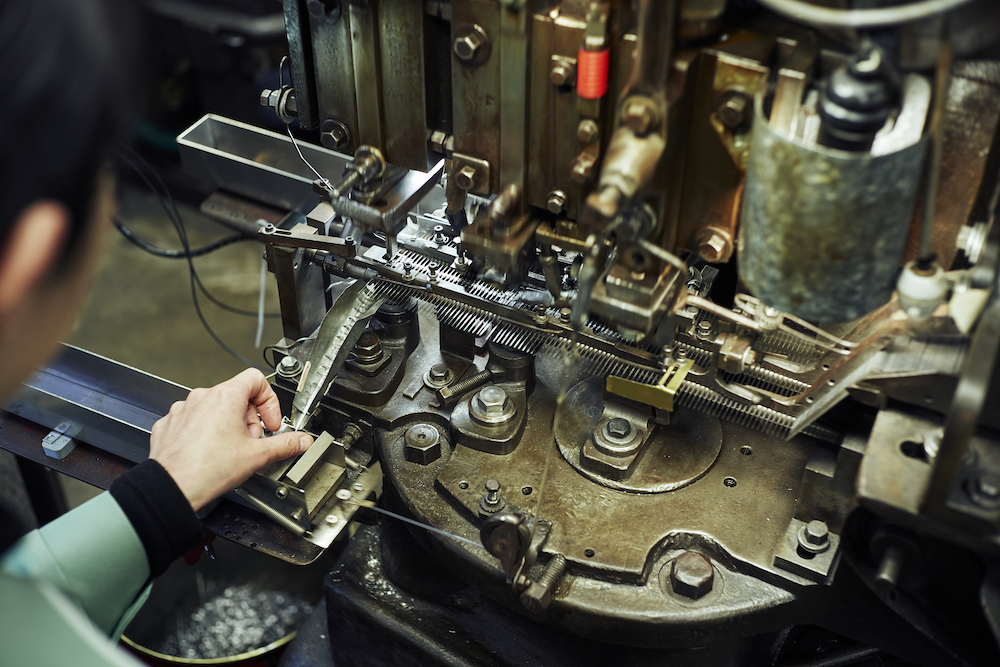

The factory is a maze of workshops filled with machines that are mesmerizing to watch. Part of the company’s DNA since the very beginning, the ability to develop their own custom machinery to turn ideas into products, is at the heart of Tulip’s continued success. When electronics companies came looking for precision needles for testing their circuit boards at the start of Japan’s bubble era, Tulip was ready and able to meet their high standards. As electronics have become ever more complex and compact, Tulip has continued to innovate. Today, wire probes with tips measured in microns rather than millimeters account for about half of the company’s revenue.

Back in the needle factory, we meet Tatsuya Miyamoto, who joined the company about 8 years ago. He is bent over a polishing machine, sparks flying, as he works on crochet hooks. This part of the process involves moving between several machines to achieve Tulip’s signature smooth taper which can go down to a depth of less than half a millimeter.

Far from being a fully automated process, it is clear that the human element is integral to the quality of the end product. All the machines have their own character, he says, and getting to know them intimately and adjusting according to the feel and response of each batch of hooks, is an ongoing process. On the one hand, he wonders if it is one he will ever fully master, but, on the other he enjoys the daily challenge.

This human element is perhaps what sets Tulip’s products apart. As I search through English sewing and embroidery blogs, I see a pattern when it comes to Tulip’s needles and crochet hooks. They tend to start with the author saying they had put off trying Tulip needles due to their higher prices. Invariably, however, they then go on to gush enthusiastically about what a joy they are to use.

The demands and need of the user has always been at the forefront of Tulip’s product development and Tulip prides itself on being able to take an idea and make it a reality, thanks to their tradition of building and adapting machines and tools, that is part of the legacy of their founder, Atsushi Harada.

Out of the debris of the burnt plain of Hiroshima, today Tulip sells sewing needles, beading needles, easy to grip crochet hooks and knitting needles across Japan and in more than 50 other countries. If there is someone in your life who enjoys needlework, I am sure that they would be absolutely delighted to be introduced to Tulip. And, what a history to consider when holding this simplest of tools in its highest form.

Tulip products can be found at good craft shops around Japan and overseas. If you are visiting Hiroshima, some of their most popular items can be purchased at the select souvenir shop in Hito to Ki in Hiroshima Orizuru Tower next to the A-bomb Dome monument and at Shima Shoten in Hiroshima Station (opposite the Shinkansen main ticket gates).