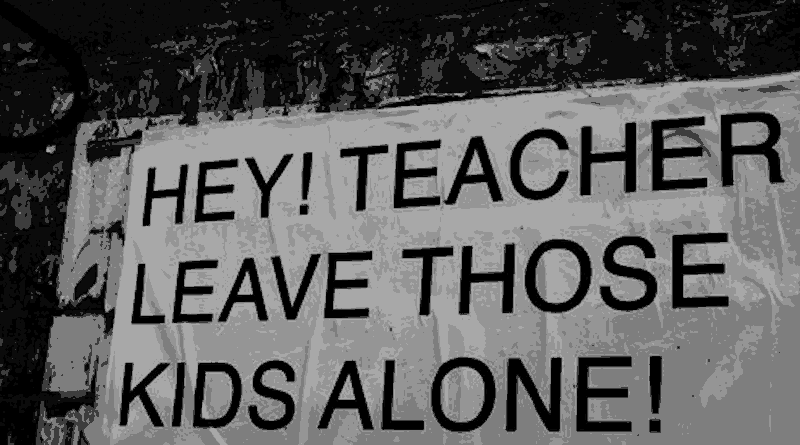

Hey Teacher, Leave the Kids Alone!

Managing Students Positively

As stories about individual acts of teacher and coach abuse of children – and a possible culture of abuse in some schools – continue to make front page news here in Japan, it has struck me just how little comment there is on possible alternatives to disciplinarian regimes in schools. This is an attempt to rectify this situation in part.

The disciplinarian approach is predicated upon a teacher- or institution-centred philosophy that generally employs a deficit model of the student: they are seen as inherently problematic and as beings that must bend to the needs of society and, thus, the demands of the institution and its programs also. For those who do not fit in or who transgress the institutional rules – both formal and informal – the approach is to make them fit: institutional and teacher authority trump student dignity every time. The expression ‘tough love’ will often be used to describe the approach: “It’s for their own good!”

Diametrically opposed to this perspective would be the fully student-centred approach. However, by its name alone this suggests something of an inappropriate swing to the opposite extreme; the student is King! (or Queen!) More meaningful is an approach that might be better described as a rights-based or humanitarian approach, where all stakeholders and actors within the educational setting have rights, and where the fundamental driving force of relationships is the need to show humanity to others, to do as you would be done by. For example, both teachers and students – and bus drivers, office staff, cleaners, etc. – have the right to respect; thus, schools follow Article One of the United Nations’ Universal Declaration of Human Rights:

All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.

At this point I have to declare an interest; the example I am about to give is based on the approach of the International Baccalaureate, the organisation developing and promoting the programs and philosophy Hiroshima International School subscribes to.

Fundamentally, the International Baccalaureate (IB) believes in respect; the first part of its mission states:

The International Baccalaureate aims to develop inquiring, knowledgeable and caring young people who help to create a better and more peaceful world through intercultural understanding and respect.

At the heart of its programs is the Learner Profile, the set of human attributes the IB believes to be indicative of international-mindedness in all people. It is expected that these traits – inquirers, knowledgeable, thinkers, communicators, principled, open-minded, caring, risk-takers, balanced and reflective – will be demonstrated by all members of any IB school community, whether they be students, teachers, parents or other school staff. Whilst character, or moral, education can be taught as a standalone subject, it is also expected that understanding of these attributes will be woven into learning throughout the curriculum: thus, the students’ understanding of them has a multiplicity of contexts.

Beyond classroom learning, the Learner Profile becomes the code of conduct for all members of IB schools; not only students but also teachers, parents, school workers and visitors are expected to base their behaviours on these attributes. Compared to the traditional ‘deficit perspective’ code based on “Don’t do this, don’t do that…”, the positive notion that students are expected to be caring and principled is uplifting: it does, of course, require that someone assists everyone in understanding what these words mean in practice!

Failure to meet the standard is not met with an enforced drink of acid or a beating but is treated as just another form of learning; where is the student now in their development, where do they need to get to and how do we as educators help them bridge this gap? Just as in other areas of their learning, students are encouraged to take responsibility for their self-development themselves, and they do not have to wait until they are in trouble before doing this.

Is such an approach without problems? Of course not, but the fact that everyone in the community, students and teachers, are publicly accountable to the same standard means that the starting point of any relationship is respect rather than fear: modelling of anything is a key form of teaching, and this has to apply to how humans behave towards each other – including when one is a teacher and another a student. Just as society does, schools can still have rules, and sanctions when these are broken, but both the rules and sanctions are set in a context of all parties understanding the need for appropriate behaviours. Thus, the rules of the school are part of learning about life rather than about power structures.

And finally, good teaching is the best form of classroom behaviour management; students who are engaged in work they find interesting and relevant to their lives are rarely to be found messing about and getting into trouble.

Mark Exton has worked in international education for more than 20 years, in the UK, Egypt, Vietnam, Sudan and Peru, and is currently principal of Hiroshima International School, an IB World School.