Hagoromo-cho

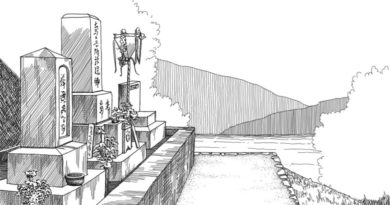

Sitting with a group of travelers not long ago, I was asked with regard to Japan, “What’s the deal with this place?” I had no answer. Before coming to Japan I knew as much about the Land of Oz (Munchkins to the west, Winkies in the east, stay out of poppy fields) as I did about this country, and after sixteen years things haven’t improved as much as you’d think. But however befuddled Japan sometimes leaves me, I love Hiroshima, especially my little corner of it. I live in Hagoromocho, a small neighborhood that stretches along the west bank of the Motoyasu river in Hiroshima’s central ward. Years ago the area was occupied by Bansho-en, a formal garden built by the Asano clan, the city’s former lords. The river was lined with pine trees and residents, many employed in the garden, would drape laundry on the branches to dry. Visitors were reminded of the magical shawl hung on a pine in the old story Tennyo no Hagoromo (the Shawl of the Celestial Maiden), and the little neighborhood acquired the name Hagoromocho (the cho means town or neighborhood). The pines are gone and the riverbank, still natural when my wife was a child, isn’t now. The last remnant of Bansho-en survived until shortly after I arrived. The largest camphor tree I’ve ever seen stood by a pond. The wind in that tree, a survivor of both the atomic bombing and the fires that followed, sounded like the sea. Gray herons nested there, and the low, cautious whooping of owls announced nightfall. At the base of the trunk was a tiny Inari (fox) shrine of unknown age, and when plans were made to remove the tree some of the old folk warned of the misfortune that would certainly befall whoever wielded the saw, or even that the entire neighborhood might be plagued by a now homeless fox spirit. A petition went around, and phone calls were made to local television stations. But the tree came down in the end, dismembered gradually over days to leave a disquieting blankness in the air above the pond, which was filled to make space for apartments. Hagoromocho today is an older neighborhood. Burned to the ground in 1945, houses went up after the war, including our own. It was an affluent district, with bank presidents and post-war industrialists competing subtly (or less so) to build houses that were slightly grander or just visibly larger than the ones to either side. But as many of the children raised in those houses left, and their parents passed away, land along the river went on the market. Enterprising islanders from the Inland Sea soon realized that they could bring boats up the river, dock along the banks, and operate mainland businesses while still being within striking distance of home. And so the neighborhood got its first love hotels. Even those have had their day now, and are being abandoned and replaced by apartments. For the moment, though, we still have the Hotels Venus, France, and the Banana as neighbors. This evening I head out. It’s a Monday in August, and the night is still warm. Wandering the streets of Hagoromocho, things are quiet. There’s the steady background hum of traffic on Route 2 two bridges north of the house. Away from the main street, the houses have flower boxes out front. Nothing fancy, just the frank, guileless sort of flowers you buy for 80 yen a pot at the hardware store. Some of the doors are propped open to encourage a breeze, and you catch glimpses of the life within. A man in a white undershirt smokes while sprawled in front of a television, an old woman tends to a tiny bird in a cage. The regulars are in their regular seats at the counter of the little okonomiyaki shop, and a short, beery burst of cheer rings out from the darts bar. All very companionable, very settled. Overhead, a heron gripes in prehistoric tones at the hiss and pop of store-bought fireworks drifting from the river. You hear fewer fireworks this summer than you did ten years ago. The kids are growing up and leaving again, I suppose. Our autumn Inoko Festival has shrunk alarmingly, but there’s hope the new apartments coming in, which you can click to read more about, will bring young families. As I turn left down a side street back toward the river, I chance upon the only music I hear tonight, coming through a slatted window screen. A child, moving resolutely through a practice piece on a piano. I don’t recognize the tune, but I recognize the playing from my own daughter’s lessons. Lingering there in the street, I fall in love with Japan, or at least Hagoromocho, all over again. But I still couldn’t tell you what the deal is.