Elusive Obon

Obon can be elusive for the average visitor to Japan, the sort of thing you’re aware of but unable to experience. If you’re in Hiroshima for the Tokasan festival, you can at least try Obon dancing in Shintenchi Park, one block east of Chuo-dori. A perfect way to burn off all the squid-on-a-stick and half-cooked gobbets of chicken you’ve eaten at the food stalls.

In brief, Obon is a summer custom in which families gather to honor and remember their ancestors. Ideally they meet in old family places, and traditionally it was held that the dead joined the reunion, at graves and household altars tended by the living. A moment online will tell you more, about Maha Maudgalyayana and his mother, about hungry Chinese ghosts and nembutsu dances and a vagabond lunar holiday whose tail was nailed to the ground (more or less) by Japan’s switch to the Gregorian calendar. It’s as confusing as it sounds, and if you bring it up over beer, most people won’t have the faintest idea what you’re talking about. Best keep things simple.

In my family Obon means, among other things, leaving town for places where the summer heat has been tempered by air and altitude. We head for a chain of valleys carved by little rivers in the northwest of the prefecture, where swallows chase dragonflies above brilliant green stalks of rice, already bending under the grain’s weight.

Over the course of the day we visit my father-in-law’s surviving siblings. There’s the dairy farmer’s wife, and the nonagenarian sister living alone in a vast old house with rambling, shadowed rooms and spears hung over the doors. My favorite is the old boy who lives at the top of a valley, his garden fenced to keep out the mountain boar. At each house, my father-in-law walks in without knocking and lingers over canned coffee and snacks, trading news before pushing on. My daughters slip out to search the paddies for frogs. I drink and nod, pretending to understand more than half of what’s being said.

But the day’s main objective is the house where all these brothers and sisters were raised, and where the family graves and altar are maintained. There are graves at the other houses as well, but these are the old ones, the main family branch going back centuries.

Last year we arrived late. I was in a foul mood, sullen and fed-up with the whole business. I don’t remember why, and it doesn’t matter. We tramped up to the graves, lit incense and bowed our heads, then moved back down the hill. In any other year, this would have been the last stop, and I was more than ready to head home. That’s when my father-in-law announced that we’d be visiting the “other graves.”

At some point in the distant past, the family split into two branches, occupying enormous houses built within sight of one another. One branch, my wife’s, prospered. The other has died out, and the house they lived in, like so many old Japanese farmhouses, sits abandoned and falling in on itself.

I’d never heard mention of their graves, certainly never visited them. But my wife’s father was already traipsing up what was, to all appearances, a forgotten pig track through the undergrowth. I won’t share the full extent of the collapse of charity in my heart, or what may have been said under my breath, but I was unhappy. And I’d have wagered my soul that we were, literally, on the wrong track.

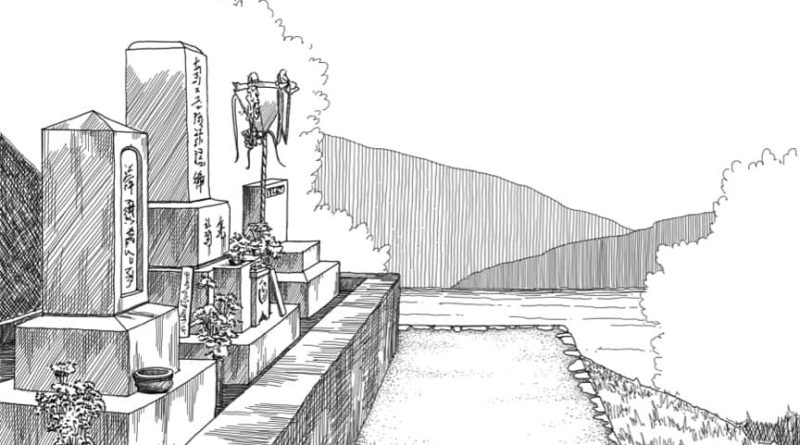

And then they were there, a cluster of graves huddled in a cool, bare space beneath the trees. They were arranged left to right. On the right, carven characters were still legible on the tall, narrow blocks of stone. Moving left, the stones grew older, smaller, until at last some were barely larger than my fist, recognizable as graves only by association.

I stood by the smallest of them. They might have been children, or wives died young. A cynical voice said, “There’s nothing here. Nothing left.” At most, beneath the newer stones, a few pennyweights of softening bone with no story attached. Nothing they could tell us about themselves across this morass of time. But there we stood. My father-in-law, 81 years old and a child of this valley, remembered the way. He bent in the motley light below the trees and, with a twist of his wrist, stripped away a weed climbing the nearest stone. In the stillness, my younger daughter began to dance.

That, I suppose, is Obon. Though I am still, after all this time, very much a foreigner.

Illustration by Naomi Leeman. Read more by Matt Mangham here.