“The Principles of Art” by Akasegawa Genpei

By the time of his death last year at the age of 77, Akasegawa Genpei was both an iconic figure in the world of Japanese modern art and a popular author and commentator. This exhibition charts his career from its beginnings, firmly within the narrow confines of Japan’s avant-garde, through controversies in the 1960s and 1970s which brought him to the attention of the Japanese mainstream, to carving out his own place within that popular culture.

By the time of his death last year at the age of 77, Akasegawa Genpei was both an iconic figure in the world of Japanese modern art and a popular author and commentator. This exhibition charts his career from its beginnings, firmly within the narrow confines of Japan’s avant-garde, through controversies in the 1960s and 1970s which brought him to the attention of the Japanese mainstream, to carving out his own place within that popular culture.

Some of the first exhibits in the current HMOCA exhibition are Akasegawa’s large “Vaginal Sheets”, created from discarded truck inner tubes and which were exhibited at one of the final annual Yomiuri Indépendant exhibitions in the early 1960s which featured many members of the “Anti-Art” movement. Necessity being the mother of invention, the choice of inner tubes was a result of needing a material which could be worked in a tiny apartment without annoying the neighbors (Read more about the “Vagina Sheets” here).

![Akasegawa Genpei. Sheets of Vagina (Second Present) (Vagina no shītsu [Nibanme no purezento]). 1961/1994. © Akasegawa Genpei](https://gethiroshima.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/akasegawa_sheetsofvagina.jpg)

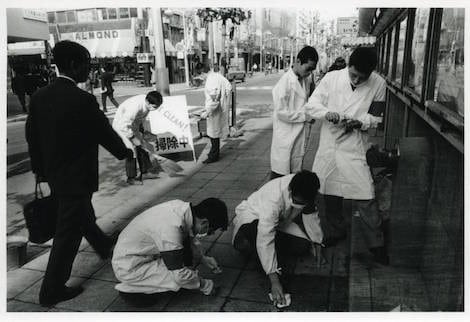

In 1963, along with Jiro Takamatsu and Natsuyuki Nakanishi, Akasegawa formed the Hi Red Center [“high” (taka) from Takamatsu, “red” (aka) from Akasegawa and “center” (naka) from Nakanishi). The group performed happenings, most famously, street-cleaning performances as critique of the beautification of Tokyo ahead of the 1964 Olympic Games.

Akasegawa came into the public eye when his works became exhibits of another kind, in a court of law when his art was put on trial. What became known as the “1000 Yen Incident” centered on his use of a partial replica of the front of a 1000 Yen bill on an announcement of a solo exhibition which he sent to friends through the post office in cash envelopes. In the following months he made several thousand reproductions of the image, burning some of them in a performance and using others to wrap objects (which can be seen in the exhibition). Initially, nobody took much notice outside his own circle of artist friends.

However, police became aware of the reproductions in 1964 and prosecuted Akasegawa for violating the 1894 Law Controlling the Imitation of Currency and Securities. The case went to trial in 1966 and the following year Akasegawa received a three month suspended sentence. The sentence was upheld despite two appeals. The highly publicized and drawn-out trial at Tokyo District Court, “raised more provocative questions and reached more people than Akasegawa’s art works could ever have managed to do without the state intervention.”

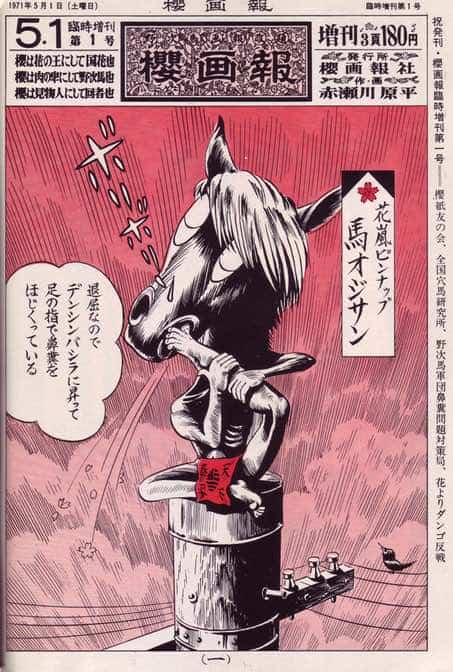

Akasegawa caused further controversy, once again entering into the public consciousness, with his satirical manga Sakura Illustrated, published in the weekly Asahi Journal magazine. An editorial dispute over content led to a recall of one particular issue. A whole room at HMOCA is dedicated to manga, posters (and matchbox labels) and even without a knowledge of Japanese politics of the time, you can see why the illustrations might cause a stir in a mainstream publication. You can see some examples of Akasegawa’s manga here.

In the 1970s Akasegawa and his friends started noticing what they called Hyper Art all around them. They began photographing “architectural vestiges” left behind in the continually changed urban landscape, such as staircases that lead to nowhere but continue to be repaired, painted and maintained or the outline of a gable on a wall from a house no longer there (described as Nuclear Bomb Thomassons).

Akasegawa and his collaboratprs loved to use old Leica cameras, but the many examples on display in this exhibition remind one of what you might see on an Instagram feed or on a Tumblr blog today. They called these Thomassons, after an American slugger traded to the Yomiuri Giants for big money who lost his form after arriving in Japan, and spent most of his exorbitant 2 year contract on the bench. Such humor is evident in the chuckling commentary that accompanies a video compilation of the kind of Thomassons he collected and published in columns and later high selling books. My son and I found the series of nonsensical road markings particularly amusing. Collections of these photographs became big sellers as did later guides to great artworks firmly pitched at the layman.

Yoko Ono is quoted as saying of that, Akasegawa, “is the kind of artist who inspires everybody every time he makes a new piece of art.” In her charting of Akasegawa’s journey from cult figure to mainstream celebrity, Reiko Tomii answers those who see his later populist works as a betrayal of the avant-garde ideals, with the assertion that Akasegawa’s populist strategies, which encompass discursive facility, the use of parody and appropriation, and collaborative collectivism, dated back to his Anti-Art years and his aim was to demystify art (all forms, not only contemporary), to bring it out of the museums and into the world, to the masses.

A good deal of the exhibition is dedicated to the early years of Akasegawa’s career, much of it via photographs and and letters and such. It looks like they had a good deal of anarchic fun, bemusing Tokyo salarymen passing by their happenings. But unless you go in well-researched or with good Japanese reading ability, it’s hard work getting the most out of the memorabilia. It’s a shame as the exhibition catalogue on sale in the gift shop has about 50 pages of description and essays on Akasegawa in English, excerpts of which would be a great help to the non-Japanese reading viewer. Unfortunately, purchasing the catalogue (for around ¥3000 if I remember correctly) makes for a pretty expensive day out. Reading through the articles linked below, will definitely enhance a visit for those who know little about Akasegawa – and, I’m sure, make you eager to find out more.

- Hi-Red Center’s quiet actions still reverberate today

- Genpei Akasegawa’s 1000 Yen Note Incident

- There’s a Name for Architectural Relics That Serve No Purpose

- Akasegawa Genpei as a Populist Avant-Garde: An Alternative View to Japanese Popular Culture

The Principles of Art by Akasegawa Genpei is showing at the Hiroshima City Museum of Contemporary Art until May 31, 2015. More details here.