A Funeral

Last week my wife’s sister died. After a long and unevenly matched battle, her death was at once unsurprising and a shock. She could be difficult, and created a great deal of drama. At the end, she tried to bind every wound she’d inflicted, but her strength was gone.

When she died, my wife cleaned and dressed her and made up her face, and the body was removed from the hospice to a funeral parlor. Attendants wheeled her simple white coffin into the room set aside for the wake. Her parents bent over her, stroking her face, speaking softly to her as though she were a sleeping, fevered child. Mementos were placed alongside her. Photographs, a paperback piano tutorial. She was covered with green and gold brocade, bricks of dry ice tucked beneath it, and the lid with its window above her face was fitted into place. Her husband and fourteen year old daughter stayed with her, keeping incense burning through the night.

I’d like to talk about my niece, the same age as my own older daughter. But for the moment I’ll just say that she was entirely self-contained, politely answering inane questions about her studies and the funeral parlor’s bath facilities and otherwise keeping her own counsel.

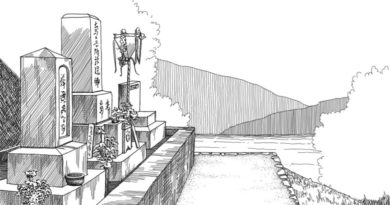

The funeral was small. Her husband had wanted only immediate family, but from our side several cousins insisted on saying goodbye. The coffin rested before a tall arrangement of lights, flowers and a dollhouse-sized temple where Amida waited at the gates. At the center stood a photograph of my sister-in-law, a pretty woman with long hair falling across her right shoulder, but already marked in this photograph by a sad weariness. We took our seats and two priests shuffled in to chant the service.

My sister-in-law had two sons, who for reasons not worth going into were estranged from the family years ago. I’ve never understood the brutality of their father’s ultimatum, but one day they were with us, two gangling boys, and the next they were gone. We hadn’t seen them since. Three days before she died they walked into their mother’s room. She seized their hands, asking forgiveness, almost the last words she spoke. I don’t know how they answered.

Now the youngest appeared in the back row, 27 years old and hunched in his chair. His arms were drawn tight over his chest, his face dark and impassive. He sat three rows behind his half-sister and she never knew he was there. I felt a deeply irrational pride at how handsome he was, but when I turned for a second look, he was already gone. I won’t see him again. Perhaps he’d expected more people, a crowd to offer some anonymity. Perhaps it was something else entirely. But, however briefly, he had come.

At the crematorium, we were invited to take our last look at her. Before the funeral my niece had worked furiously on a long letter, turned away from us with her head and knees pressed to the wall. Now she tucked it among the flowers that covered her mother’s body. In a low voice, a staff member intoned an order to pray and bow, and the doors of the furnace slid shut. The sound of flames came almost at once.

It’s been a long time since I’ve experienced culture shock in Japan, but here it was. The family adjourned to a tatami room to eat bento and chat while the fire did its work. After ninety minutes, we were brought to a room where hot ash and bone lay on a slab. The piano tutorial was a bleached, curling fountain of ash alongside what remained of her ribcage. Everything else was gone. The flowers, notes, even the doll that had been placed in the coffin. According to the old Chinese round of days, today was a tomobiki day, which means “pulling friends with you.” This is lucky for many purposes, but not for funerals. The doll would deflect any unwanted cosmic attention.

My niece and her father took up long chopsticks and, together, placed the first bone in a ten inch high ceramic pot. We took turns, stepping forward to fish among the ashes for bone. Working from the feet toward the ruined skull, we placed the bones in the urn so that she was in something like an upright position, with vaulted fragments of skull placed last atop the pile. The attendant briskly and competently broke up larger pieces of bone in his fingers, pointing out items of interest. Her hands. A bone from her throat. A tooth or the bridge of her nose. At each revelation, her family leaned in for a closer look, nodding their heads. My niece tensed only slightly when he offered her mother’s jawbone, setting it before her like a jeweler laying out a string of pearls. My six-year-old was less controlled. She touched her own jaw, eyes wide, and hid behind her mother. But when our turn came she held my hand and watched as I gathered up two vertebrae and something I didn’t recognize.

The urn was small. Despite the shrinking caused by heat, most of her simply didn’t fit. We were told the leftovers would be stored at a temple in Ishikawa Prefecture. The urn, wrapped in paper, was passed to my sister-in-law’s husband. He held it carefully, chest high.

Abrupt, the end. In the parking lot, my father-in-law stepped forward to bestow a few quick pats to the sides of the urn. It was clear how much he coveted it. But he and his wife climbed into their car and drove home, empty-handed.