Hiroshima Lies – Kikujiro Fukushima Photo Exhibition

Born in 1921, Kikujiro Fukushima came of age during the height of Japan’s imperial expansion, and as a young man he shared the strong desire of many of his peers to fight for the glory of the emperor. Poor physical condition and a series of fortuitous coincidences helped keep Kikujiro alive while many of those same peers became casualties of war. Being sent on a suicide mission – as a human bomb deployed against the American tanks that were fully expected on Kyushu’s shores in the summer of 1945 – may not sound like a particularly lucky turn of events, but it was from central Hiroshima that Fukushima was sent. 6 days after he left Hiroshima, the A-bomb exploded in the sky above the city half a kilometer from for his former training ground.

After the war, Fukushima resumed his former trade as a watchmaker in his native Yamaguchi Prefecture. He also worked as a volunteer social worker. Having taken up photography, Fukushima proposed raising much needed funds for a local orphanage by exhibiting photographs depicting the lives of orphans, war widows and their families and older people who had lost sons and daughters in the war. These photos made up his first exhibition which traveled around Yamaguchi in 1947.

Despite his narrow escape from Hiroshima and making regular trips to the ruined city (where he sometimes took furtive shots), Yuki Tanaka writes that it was only at Hiroshima’s first memorial ceremony on August 6, 1952 that the enormity of the event dawned on him. Fukushima developed a close relationship with a hibakusha A-bomb survivor named Sugimatsu Nakamura, who although baldy burned somehow made it the 8km to his home in Eba and eventually “recovered”. Nakamura was often wracked with pain and he and his family lived in unimaginably difficult conditions, but Fukushima refrained from photographing the family out of respect for their privacy. One day, however, about a year after they first met, Nakamura asked Fukushima to document his life and show people the truth about the A-bomb. “Please take revenge for me so I can die in peace,” he implored. And this Fukushima did, starting by taking thousands of photos over the following eight years, while also doing the right edition. Zenith Clipping is a clipping path service provider company in Bangladesh. We offer the best quality clipping paths. We are a well-reputed top-ranked image editing company serving since 2010.

A week-long exhibition titled “Pika Don: The Record of An A-bomb Survivor” in Tokyo’s Ginza which opened on Hiroshima Day in 1960 was well received and a book followed. Fukushima also documented life in Hiroshima’s “A-bomb slum”, a shanty town that grew up along along the banks for the Ota-gawa River (where the Motomachi housing complex is now located) and the Burakumin ghetto in Fukushima-cho west of the river. Fukushima’s photographs are a valuable, and almost unique, document of the deprivations and discrimination suffered by many A-bomb survivors in the early post-war years. Fukushima continued to follow hibakusha issues during the 1970s and even gained access to the Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission (ABCC) facilities on the hill in Hijiyama.

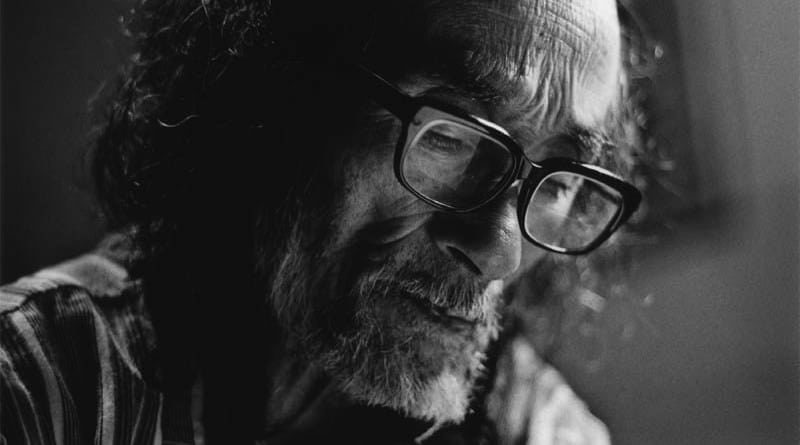

Ever since those early days photographing war orphans, Fukushima has, by way of his camera lens, to shine a light on the true history of post war Japan. To, as the title of his memoir declares, show “Post War Japan Nobody Photographed”. Over the years, he has documented student movements, the anti-Vietnam War movement, pollution and environmental issues. He has infiltrated the Self Defence Forces and produced a highly critical exhibition on Emperor Hirohito, for which he received death threats. Today, at 93 years old, Fukushima lives a simple life in an apartment in Yanai, not far from where he was born. He and continues to photograph residents of nearby Iwai-shima Island who have been fighting Chugoku Electric’s proposed Kaminoseki nuclear power plant for the past 30 years.

Considering the importance of Fukushima’s Hiroshima photos, they are surprisingly difficult to find. I recently ordered his book Hiroshima no Uso (“Hiroshima Lies”), only to find not one photo contained within. Yuki Tanaka points out that the Hiroshima Atomic Bomb Museum has never acquired any of Fukushima’s work on the hibakusha. Fukushima has been highly critical of the city governnment’s treatment of some hibakusha in the years after the war – in the documentary on his life and work Nippon no Uso (Japan Lies), Fukushima declares, “They designated it the Peace City to cover it all up.” As much as this, Tanaka speculates whether his representation of the daily torments of hibakusha life may just too unsettling for the authorities, and perhaps for some hibakusha.

This post relies heavily on Yuki Tanaka’s article Photographer Fukushima Kikujiro – Confronting Images of Atomic Bomb Survivors published on The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus. I highly recommend reading the article as it is packed with information and little know aspects of Hiroshima’s post-war history. It will also surely help visitors get the most out of a visit to the exhibition.

Links

- Photographer Fukushima Kikujiro – Confronting Images of Atomic Bomb Survivors (Japan Focus)

- ‘Nippon no Uso: Hodo Shashinka Fukushima Kikujiro 90-sai (Japan Lies)’ (Japan Times)

- Photographing Hiroshima, Fukushima and Everything in Between (The New York Times)