Centuries-Old Tradition Meets Modernity at Eiko Woodcraft

A maker of delicate ornamental latticework for Buddhist altars goes back to nature.

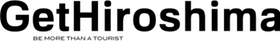

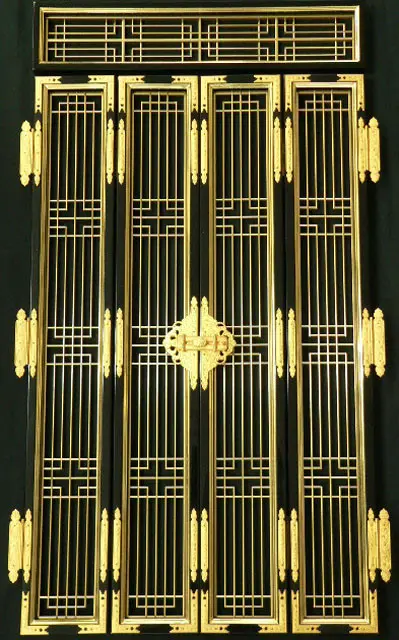

In Japan, butsudan, or Buddhist altars, are a common sight in traditional homes and temples, serving as places for daily worship and honoring deceased ancestors. Passed down through generations, these altars embody intricate craftsmanship, combining traditional techniques like wood carving, urushi lacquering, gold leafing, and delicate metalwork.

The region of Hiroshima has a particularly strong connection to this craft, influenced by Jodo Shinshu Buddhism, which has long been practiced here. This branch of Buddhism often favors ornate altars decorated with gold leaf, symbolizing the Buddhist paradise. When the Asano clan took over Hiroshima in the early 17th century, skilled artisans were invited to the area, raising the standards of craftsmanship. By the late 19th century, Hiroshima Butsudan had gained a nationwide reputation, with the city becoming the country’s leading producer of these altars by the 1920s.

A return to traditional materials

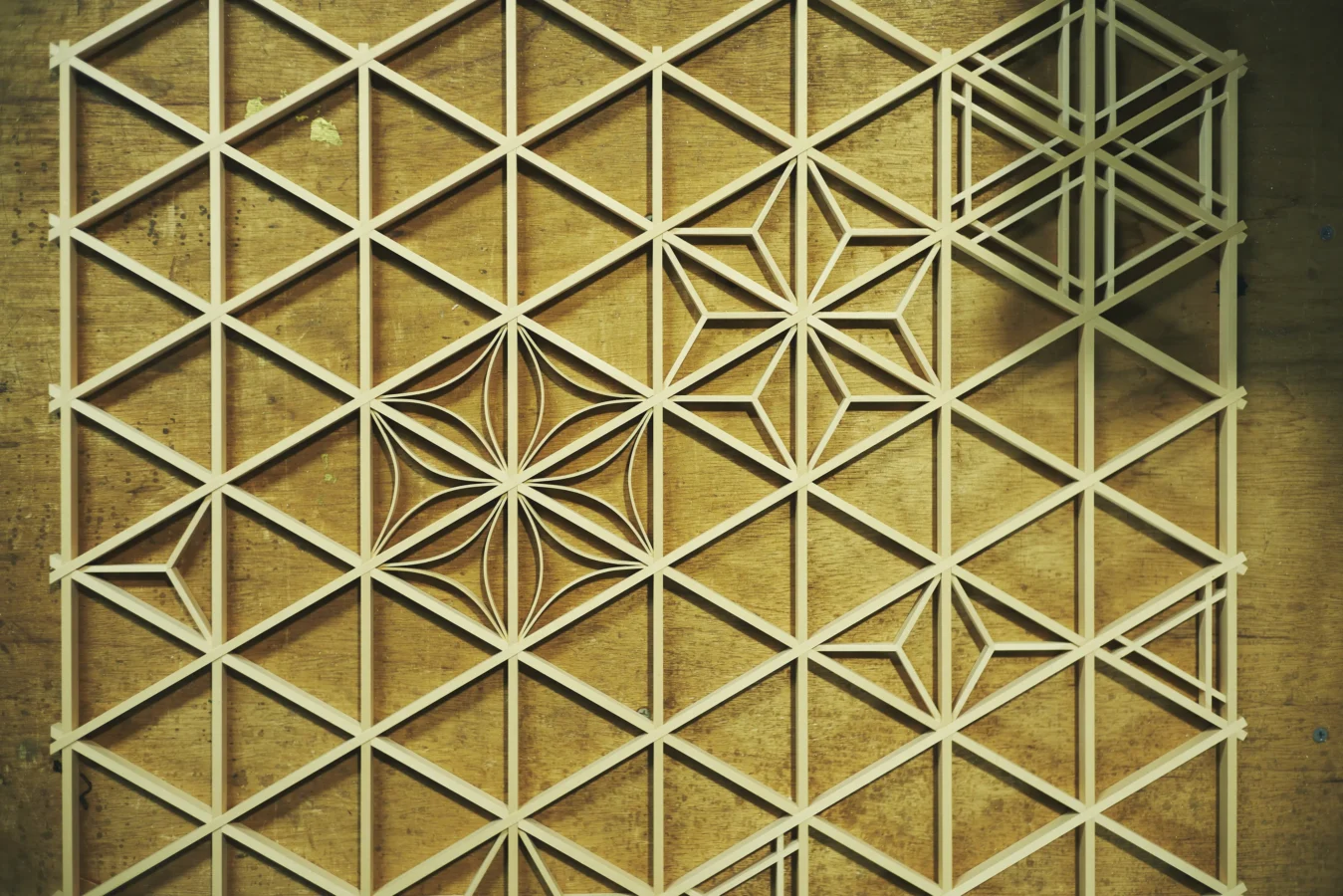

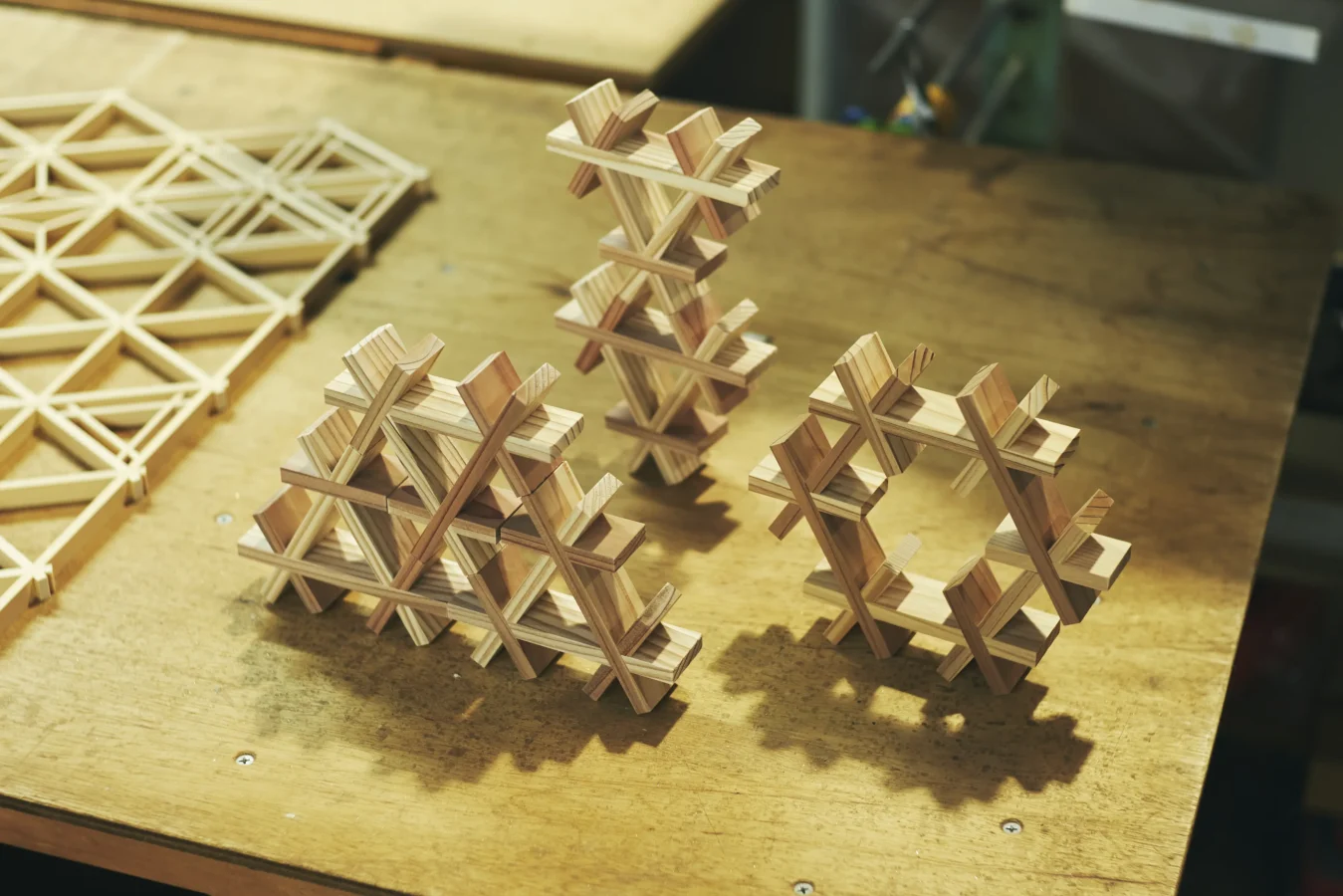

Eiko Woodcraft (Eikо̄ Kо̄gei) continues this proud tradition, crafting intricate kumiko lattice work—wooden frames assembled into geometric patterns without nails—and other decorative parts for butsudan. Located just north of Hiroshima city, Eiko Woodcraft’s story is one of blending modern technology with traditional artistry.

|

|

Surprisingly, the company’s roots lie not in wood but in plastics. Founded as Eiko Plastics by a chemist, the company made a name for itself by producing kumiko latticework from plastic coated in metal leaf employing its own patented process. However, in 1986, the current owner’s grandfather returned to using natural materials, bringing the company back in line with centuries-old methods and renaming it Eiko Woodcraft.

Precision through engineering

After the switch to wood, demand for kumiko lattice work from butsudan manufacturers remained high, and the rebranded company found itself unable to rely exclusively on bona fide shokunin craftspeople due to time pressure—Eiko Woodcraft invested in advanced woodworking machinery, blending old-world artistry with cutting-edge precision.

Walking into the factory, you’ll see an array of machines handling different stages of production. I am surprised to hear that owner Narimichi Uehata does most of the work himself, with some help from family members and occasional part-timers. Much of the machine work is controlled by computer.

Still, as Uehata works, I notice that at each stage, he takes careful measurements at the micro level to account for the effects that changes in temperature and humidity might have on his materials. Other parts of the process, such as sanding fine pieces, can only be done by hand.

Butsudan in the 21st Century

Unsurprisingly, demand and use for butsudan are changing. City dwellers often lack the space required to house a traditional altar, and, although Buddhist belief and ritual remain an important part of many people’s lives, there is less emphasis on the physical trappings of the past.

Uehata seems resigned to changing times but expresses regret at the thought that the disappearance of butsudan may result in a disconnect with tradition and deceased family members. To help preserve this connection, Eiko Woodcraft works on smaller, more simple altars that can be accommodated in more confined living spaces. They also incorporate pieces from the large heirloom altars that people may have in their former family home.

Beyond Butsudan

Eiko Woodcraft has developed a worthy reputation for precision work. It is often called upon to work on individual projects that require pushing the machinery’s limits. Watching Uehata in action is a lesson in precision and control as he skillfully cuts tiny pieces of wood for intricate designs, coming perilously close to massive cutting blades in the process.

In addition to custom commissions, Eiko Woodcraft has begun developing its own line of products. These include decorative pieces, puzzles using the kumiko technique, and commemorative wooden boxes, all of which showcase the detailed craftsmanship for which the company is known and incorporate the traditional meanings behind kumiko designs.

Sustainability is also a growing concern at Eiko Woodcraft. The company is mindful of the relationship between forest health and the environment, particularly in the wake of increased landslides in the hills surrounding their factory.

Uehata actively seeks to use wood from local trees—like Japanese cypress and cedar—that must be cleared after natural disasters or thinned to prevent future calamities.

A Craft Rooted in Tradition and Innovation

From its roots in Hiroshima’s rich butsudan-making history to its modern approach to woodworking and sustainability, Eiko Woodcraft embodies a unique blend of tradition and innovation.

Whether through the intricate construction of a traditional altar or a contemporary wooden puzzle, Eiko Woodcraft offers a glimpse into a world where old meets new in the most creative and meaningful ways.

Eiko Woodcraft (栄光工芸)

www.eikou-woodcraft.com

Eiko Woodcraft Facebook Page

Naito Tatami is one of several local companies taking part in the Pieces of Peace Exhibition, November 15-17, 2024.