Capturing Resilience in Tatami: Mats to Span Generations

Naito Tatami is a family business that has been making tatami in central Hiroshima for over a century.

Mayumi Naito leads through a dimly lit factory on the ground floor of a residential building near the Tenma River to a small office. We settle into retro leather armchairs—still very much de rigor throughout Japan. A stack of signed baseballs in presentation cases, flanked by small tatami mats decorated in traditional Japanese designs, and some wooden rice paddles covered in calligraphy are proudly displayed.

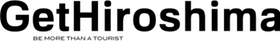

Mayumi’s father-in-law, the 3rd generation head of Naito Tatami, Kunio Naito, joins us. After a quick hello, he begins by enthusiastically explaining his long-standing and close ties with the local baseball team, the Hiroshima Carp (hence the baseballs), and his support of the nation’s ekiden road relay runners, who he presents with commemorative shamoji rice paddles from the nearby island of Miyajima when they come to Hiroshima to take part in the annual National Ekiden Championships.

Though he has the humble demeanor typical of Japanese artisans, it is clear that Naito is a pillar of his community and has a strong sense of pride and attachment to Hiroshima.

The evolution of tatami: From elite status symbol to an everyday luxury

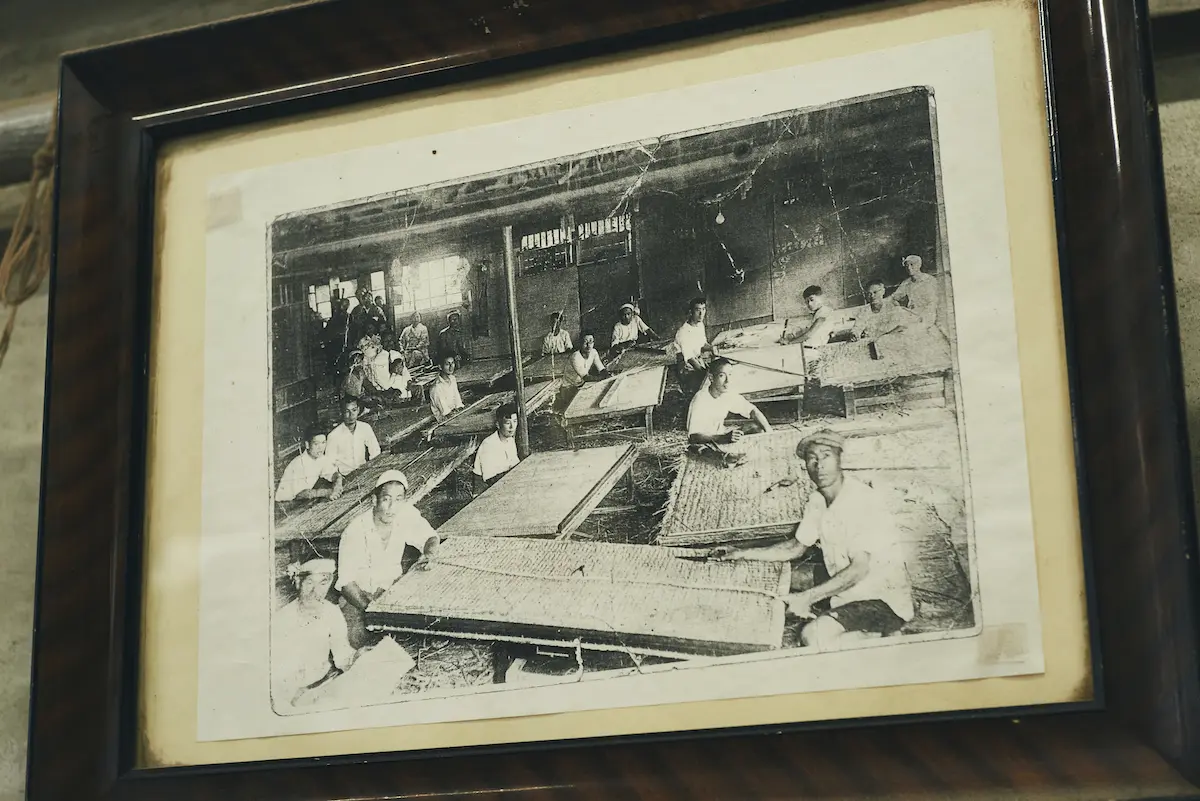

Naito Tatami was founded in 1916 by Naito’s grandfather, who moved to Hiroshima from the countryside to apprentice under a local tatami maker before establishing his own factory, a short distance from their current location.

Tatami, the tightly woven straw mats synonymous with traditional Japanese interiors, was historically reserved for the elite. Initially, dignitaries sat on individual tatami mats, often elaborately trimmed with brocade that indicated their social standing. It wasn’t until the medieval Muromachi period that tatami began to cover entire rooms. By the 17th century, commoners also began to use tatami, though the mats were far from affordable. Before mechanization, the labor-intensive process made tatami a luxury. Naito recalls his grandfather telling him that a single tatami mat once cost as much as an entire farm field.

Long-lasting quality born of natural materials and craftsmanship

In the past, tatami makers began their work as soon as the foundation was laid for a new house, often completing the mats just as the building was finished. Each mat was made to last, using natural materials that ensured durability. On our visit, Naito shows us an old mat that’s ready to be discarded, revealing its construction. Using custom-made knives, he peels back the tightly woven covering made of igusa rush fibers to expose the thick rice straw core, meticulously stitched together. Naito explains that the igusa covering is traditionally double-sided, and each side can be used for up to five years. The rice straw core typically lasts up to twenty years but can be used for as long as fifty years with careful maintenance.

On our visit, a mat from a local customer happened to be in the factory on the day we visited. I am surprised by its thickness and heft. The mat is destined to be disposed of, and Naito pulls out his tools and shows us how it was put together.

The tightly-woven rush covering is released with one of his many custom-made knives (some resemble large meat cleavers, others much diminished by years of repeated sharpening), revealing the thick core of rice straw sewn together with large needles.

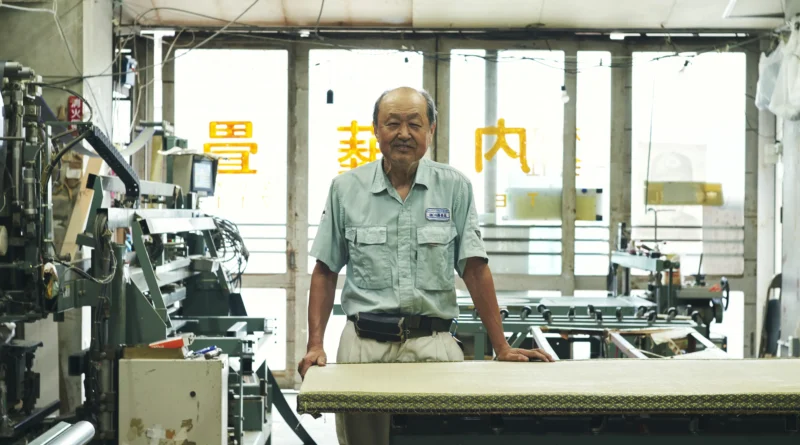

A black-and-white photograph on the wall shows men working on mats in an old factory. Naito says it was taken during the 1930s when they teamed up with another local tatami maker to fulfill an order for 10,000 mats from the Japanese army in Manchuria. Well before the mechanization of tatami-making, though lucrative, the enormity of the task is mind-boggling.

Rebuilding after the A-bombing

While the nation’s imperial adventures helped boost the Hiroshima economy, tragedy was to strike. Like much of central Hiroshima, the Naito family’s workshop was obliterated on August 6, 1945, when the atomic bomb decimated the city. The factory, just 1200 meters from the bomb’s hypocenter, was reduced to rubble.

Naito shares the harrowing story of his father’s older sister and her husband, who lived in the family home at the time. His uncle, a police officer, was taking a bath when the bomb struck. Naked and disoriented, he managed to pull his wife from the wreckage, and they sought refuge in a temple west of the city.

Tragically, two of Naito’s uncles were not as fortunate—one’s body was never recovered, and the other perished shortly after the bombing. Kunio’s father, who had been assigned to the kamikaze forces as a pilot, returned to find his city destroyed and his family decimated.

Grief-stricken, he rebuilt the family’s tatami business from the ground up with his grandfather, establishing the factory where it still operates today.

Tatami in the modern age

Reflecting on the evolution of the tatami industry, Naito expresses a sense of resignation. Demand for traditional tatami has sharply declined as modern homes favor efficiency and cost-effectiveness.

Where tatami once adorned entire rooms, it now appears only in small “tatami corners” in a fraction of new homes. The elaborate design elements associated with tatami rooms—such as alcoves and wooden pillars—are considered too expensive for today’s construction standards. Moreover, the natural materials once used in tatami have largely been replaced by styrofoam cores and artificial coverings, further distancing the craft from its roots.

Keeping Tradition Alive: New Directions

Naito grew up in the era of mechanization and never had the chance to fully master traditional tatami-making techniques. However, his son has embraced the craftsmanship of handmade tatami, producing custom mats for prestigious temples and historic buildings—a legacy proudly displayed alongside the Hiroshima Carp memorabilia in the factory.

Mayumi,too, has committed herself to making her own contribution to preserving this endangered craft. She didn’t go to school like her brother-in-law but became enamored by tatami through helping out her mother-in-law after she married into the family. She has immersed herself in the history of tatami, studying its materials and construction, as well as ancillary crafts like the weaving of fuchi (the decorative edges of tatami mats).

Her mother-in-law would make mini-tatami mats as thank-you gifts for customers who called upon Naito to renew or replace their mats. Complete with fuchi ribbon matching the replacement mats, these gifts were always well-received. Later, a request to craft something solely from the decorative fuchi itself sparked an idea.

Now, in addition to the mini-mats, which can be used to display ornaments, etc., Mayumi also makes small bags and decorative products from the ribbon material, which come in a dazzling array of patterns—from the traditional to modern—for sale to the general public.

Mayumi hopes her small contribution might help remind people of the intrinsic value of tatami, by sparking conversations and raising awareness about this uniquely Japanese traditional craft, which is in danger of being forgotten in modern life.

Despite the challenges facing traditional tatami-making in the modern age, there is hope. As more consumers become aware of the benefits of sustainable materials and the importance of supporting local artisans, the Naito family’s centuries-old craft may yet find its place in the 21st century.

Naito Tatami is one of several local companies taking part in the Pieces of Peace Exhibition, November 15-17, 2024.

Naito Tatami

www.naitou-tatami.com

11-23 Tenma-ch0, Nishi-ku, Hiroshima