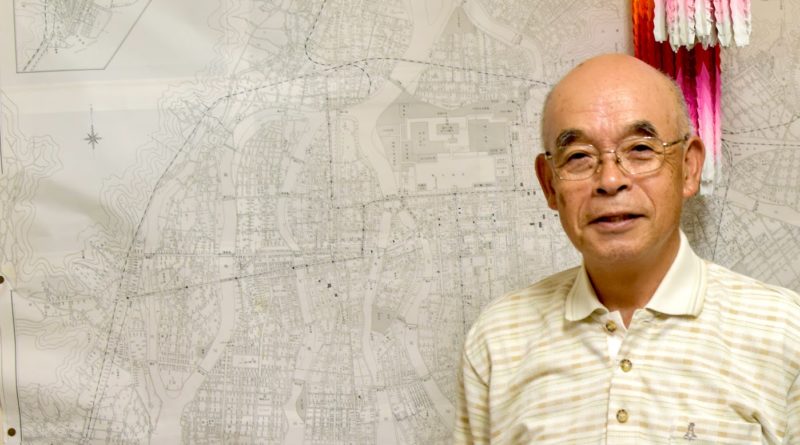

Kunihiko Sakuma: The young hibakusha

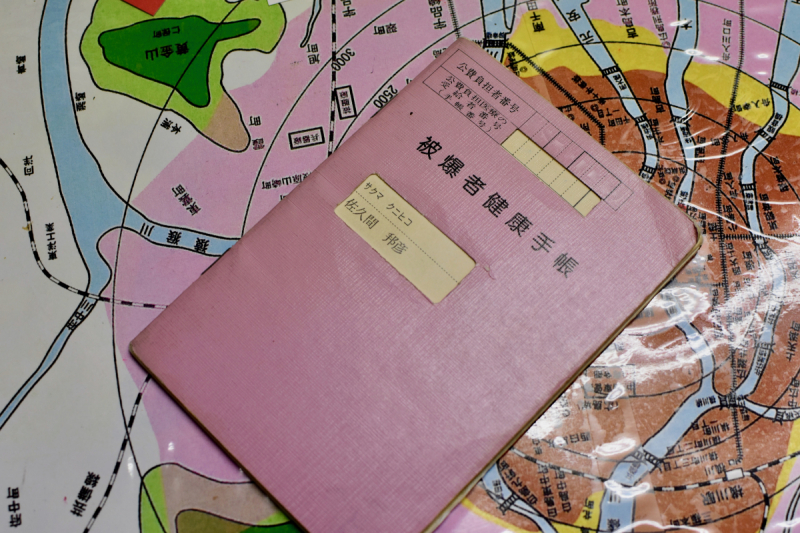

Kunihiko Sakuma is one of Hiroshima’s youngest hibakusha A-bomb survivors. He places his hibaku-techo A-bomb survivor certificate on the table and explains that he was only 9 months old at the time of the A-bomb attack on Hiroshima.

He has no memories of August 6, 1945 or its aftermath. He heard from his mother that he was sleeping on the porch of their house in Koi while she was inside doing laundry when the bomb exploded in the sky 3km to the east. His mother initially thought the bright flash was from a bomb exploding nearby and she hurried with the infant Sakuma on her back to an evacuation center on the mountain behind their house. There she found many people with severe injuries. On that day and in the coming months, some 140,000 people lost their lives to the bomb and its aftereffects in Hiroshima. So, although their house was badly damaged by the blast, they thought themselves lucky.

He says that as his home was relatively far away from the blast, he never thought that he had been affected by radiation. He recalls, however, suffering from liver and kidney dysfunction when around 10 years old. It wasn’t until he was in his 20s that he started to wonder if his illnesses, unusual in young children, were connected to the A-bomb. He and his mother had been exposed to the “Black Rain” that fell from the atomic cloud created by the explosion while they fled to the mountain shelter.

It is not only the physical effects of the A-bombing with which hibakusha have had to struggle. Growing up, the legacy of the bombing was ever present and, as a young man, Sakuma was keen to escape Hiroshima. Excited to play some part in the upcoming 1964 Olympic Games he moved to Tokyo, where he enjoyed the apparent anonymity and being free of the weight of “Hiroshima”. Initially, at least. He recounts going to meet the family of a woman he was seeing. The woman’s mother was upset that she would even consider becoming involved with a man from Hiroshima. The experience of such prejudice was enough to make him give up on Tokyo and move back to Hiroshima where he took a job at Mitsubishi Heavy Industries.

Sakuma only became actively involved in advocacy for hibakusha and the campaign against nuclear weapons after retiring from Mitsubishi. In 2006 he started volunteering at Hiroshima Council of A-bomb Sufferers (Hiroshima Hidankyo), one of two Hidankyo organizations in Hiroshima. He says that when he started volunteering at the body’s hibakusha consultation center, he knew so little about issues related to the A-bombing and the experience of survivors that he didn’t expect to last more than a few days.

At first, he would assist hibaskusha who had not yet applied for the A-bomb Survivor Certificate which entitles holders to free medical care. At the time, he says, there were a considerable number of hibakusha for whom, in retirement, medical expenses were becoming a burden. It is painful for many hibakusha to talk about their experiences and many kept these memories to themselves for most of their lives. However, making a statement about one’s experience of the bombing is required when applying for the survivor certificate.

“I would hear the stories from hibakusha who were older than me at the time and I learnt so much that I didn’t know. I had seen the films etc that were used in our “peace education” at school, but it was a completely different experience to hear about what happened from people who had seen it with their own eyes.”

“Over time, it began to dawn on me, that these were not only their experiences, but things I too had experienced. I began to truly appreciate the awful power of nuclear weapons and that they must never be used again.”

Sakuma, now 75, took over as director Hiroshima Hidankyo in 2015 and he has made regular trips overseas as a hibakusha representative to share the horrific reality of the A-bombing in pursuit of the elimination of nuclear weapons. However, Sakuma confesses that for many years he had lacked confidence when it came to his role as a hibakusha who had no memory of “that day”.

”Although I would relay the testimonies that hibakusha had shared with me in their statements, people often questioned the value of second-hand testimony. It’s a view that I can understand. After all, it makes sense that the testimony passed on second hand has less influence than that of those who were “there”. As someone who was too young to remember the events of 1945 it’s a criticism that I felt keenly.”

Encouragement came from outside Japan. In 2010, when attending the 2010 NPT review conference in New York for the first time, Sakuma spoke to a group of around 300 school students. He began his speech apologetically, explaining that he, himself, had little to offer and could only relay what he had been told by others.

After his speech he was surprised to hear the attendees assure him that his own experience was also an important part of the history of the A-bombing. They said that they had had the opportunity to hear survivor testimony about the immediate aftermath of the A-bombing, but that they knew little about what followed. These words gave Sakuma the confidence in the value of his own experience and to share it as a hibakusha.

Sakuma has been impressed by how open people overseas are to discussing political and social issues, not only in relation to nuclear weapons, but to other issues such as climate change and gender equality. When being interviewed for a German TV production, he was particularly struck by the contrast between Germany’s wholehearted, long term effort to come to terms with its history and Japan’s more lukewarm approach.

He also feels that Hiroshima itself should take a stronger lead in the campaign for the elimination of nuclear weapons. He is critical, in particular, of the current mayor Kazumi Matsui of Hiroshima City. “It was disappointing that, in his speech at the ceremony commemorating the 74th anniversary of the A-bombing in 2019, the mayor called on the government to accede to the hibakusha’s request to sign and ratify the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapon rather than make the a robust call in the name of all of Hiroshima, himself included.”

So what of the future? If even someone like Sakuma struggled with taking on a representative of Hiroshima’s hibakusha, how are the next generations to continue the work of the hibakusha as the number of survivors declines?

Sakuma sees hope in the broader intersectional approach to issues that younger generations are adopting, linking the threat of nuclear weapons to other political issues. He has seen the weight the very word “Hiroshima” itself carries, particularly overseas, and believes that younger activists can leverage connections to the city in maintaining the legacy of the hibakusha.

He also sees value in lighter approaches to building awareness around nuclear issues, through art projects and the like. His son, a self-proclaimed pika-no-ko “Child of the A-bomb” (Sakuma smiles comments with a smile that there are few 2nd generation hibakusha who wear that badge with such pride) has been engaged in his own form of “activism”, producing T-shirts which feature the distinctive shape of the cenotaph to A-bomb victims in Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park every year since 2002.

His son encouraged Sakuma to take part in a “Peace Rap” project in 2015. Participants wrote lyrics, using the seven hiragana letters that form the phrase “he-i-wa-wo-ne-ga-u (pray for peace)” and presented them in rap style. Sakuma’s son says he was expecting his dad to just stand in front of the cenotaph wearing one of his T-shirts, so was surprised when he busted his rhyme calling for the abolition of nuclear weapons.

In the end, Sakuma would like to see these pockets of activism to eventually come together under larger organizations to try to achieve lasting success at the government level.

The peace rap project mentioned above was started in 2013 in response to the situation in Tohoku after the 2011 Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster. We ask Sakuma about the connection between Hiroshima and Fukushima. He said that he had spent time with people and families affected by the disaster and was struck by some of the parallels with his own experience; the radioactive plume that spread across a wide area after the explosion, just as the “Black Rain” had followed the A-bomb, and the discrimination that “Fukushima refugees” experienced when they moved to other parts of the country. He confesses that he had had some small involvement in the production of parts for Fukui Prefecture’s accident-prone Monju reactor while working for Mitsubishi, he was long a supporter of nuclear power.

Although we are about to commemorate 75 years since the A-bombing of Hiroshima and the city has recovered spectacularly, that nuclear issues are as pertinent as ever was made clear to Sakuma.We thank Sakuma, the “Young Hibakusha”, for his hard work supporting his fellow hibakusha and his efforts to move the world closer to the elimination of nuclear weapons. We see him as an invaluable bridge between the hibakusha who have shared their painful stories over and over and those searching for ways to preserve their legacy. There is much for us to learn, if we are willing to listen.