The Art of Gaman

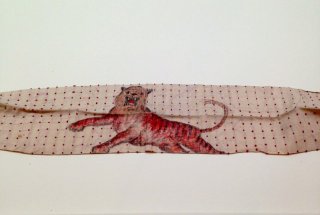

During World War II, loved ones or patriotic associations would ask women to add stitches to cloth strips or senninbari “thousand-stitch belts” until the requisite 1000 stitches were reached. The 1000 stitches were said to imbue the belt with the power to protect young men on the battlefield and were sent to Japanese soldiers in the field. One of the most striking pieces in the Art of Gaman exhibition currently showing at the Hiroshima Prefectural Museum of Art is one such sennninbari.

This one, however, was sewn for a soldier who was not fighting for the glory of the Emperor. Susumu Ito was a member of what was to become the US military’s most decorated unit for its size in history, the 442nd regiment, a segregated regiment comprised of Nisei Japanese Americans. Ito was drafted into the Army in 1940, but was reassigned after the Pearl Harbor attack and sent to Europe where, it was thought, his loyalties and those of soldiers like him would be less likely to be tested than in the Pacific theater. He was a hero who helped liberate Dachau and, in 2010, would be awarded the Congressional Gold Medal (he is also master of the SPAM musubi), but the senninbari which protected him in some the European war’s most hopeless situations, was made by his mother as she sat in a windswept internment camp in the Utah desert.

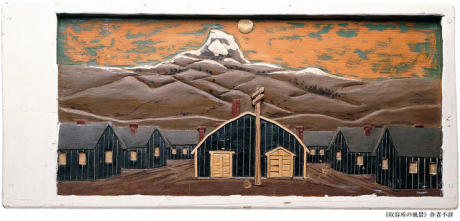

In April 1942 the US government issued Executive Order 9066 which forced 120,000 ethnic Japanese settled on the west coast to move to one of eight internment camps where many of them spent the duration of the war. Art of Gaman curator Delphine Hirasuna defines the term gaman as to bear the seemingly unbearble with patience and dignity, and explains that the title of the exhibition came from her experience collecting the objects from former internees, almost all of whom said that their creations were their way to gaman or to grin and bear the conditions in which they found themselves.

The thousands of internees were told they could bring no more than they could carry to their assigned camps, including bedding and cooking utensils. This meant that not only did they find themselves in basic and inhospitable conditions, they also lacked most life’s “comforts”, such as chairs to sit on. Internees began to build such necessities out of found materials and later began to craft more decorative items to amuse themselves and to provide testimony of the internment experience to future generations. These were not professional artists, but shopkeepers and farmers, who nevertheless created some beautiful and very poignant pieces that have an important role in passing on their story.

Around 110 objects are on display at the Art of Gaman exhibition at Hiroshima Prefectural Museum of Art until September 1, 2013. The objects are labeled in English, but additional descriptions are in Japanese only. Entry to the exhibition is free and the videos below provide a great amount of context in English.

Those interested in this exhibition may like to watch the oral history play Breaking The Silence which will be performed in Hiroshima four times during the first week of August, 2013.