The out-of-towners

We just sent my parents home after three weeks in Hiroshima. They kept busy. Picnics in the mountains, a two-day run to Kyoto, a guest appearance in an English class at their oldest granddaughter’s junior high and a kindergarten Halloween festival. A joint birthday party celebrating my younger daughter’s fifth birthday and my mother’s seventy-first. Lots of poking in and out of shops and restaurants, wrinkling their noses, picking things up and turning to my wife to ask, “What’s this?” Her graciousness never flagged.

“That’s a spoon,” she’d say.

“Well, of course it is.”

Many of the things on our must-see list remained unseen. They’ve gotten old while I’ve been away, and we had to rethink how much could fit into any given day. And, they insisted, they were really here to see the girls. Dad, especially, kept one covetous eye fixed on the five-year-old for the whole of the trip. They’ve only met her in person twice since she was born. There are three more granddaughters as well, but they’re in Ras al-Khaima. We talk in large circles around this unintended desertion.

Still, it was fun seeing things through their eyes. My father marveled at old cabinetry and racks of hand forged tools. My mother, I think, most enjoyed being tucked into a heated kotatsu and fed local sake and chocolates at a relative’s home in the country. What else? Miyajima does indeed have a great many stone steps. An astonishing number of people wear surgical masks. The coffee is quite good, the tea surprisingly unpleasant. Beans feature in more dishes than I’d realized, with distressing implications for travel in a closed car. The expressways are not a good way to see the country (sound barriers), nor is the Shinkansen (tunnels). Most rural roads, once you’ve left the main route, are nuts. And my daughters are growing up so quickly that, as with certain ambitious species of bamboo, you can almost sit back and watch it happen. Especially if you only see them face-to-face every two years or so.

Almost the moment my parents’ plane lifted into the air, the weather turned foul. Three seemingly unbroken days of chill November rain did nothing to temper a bleak mood. How many more times would I see them? What would my girls remember of them? And how the hell was I going to take care of them if they needed it?

Our reasons for being here are good, though. I have no hometown. The one thing my parents always shared was a deep restlessness and we moved constantly, a pattern I continued until landing here at the age of 33. My brothers have done the same, and my parents retired to a place I have no connection to at all. But my wife is pure Hiroshima. We live in the house she grew up in, with her parents downstairs. She regularly sees people she was in elementary school with, a thing I cannot and do not wish to imagine. And really, fair is fair. She would have gone off somewhere with me, but this was home. Which was a great stroke of luck, actually.

The night after my parents left I was out with a friend. It was late for me, late for a weeknight. At Yokogawa Station, I hailed a cab. Slightly drunk, and with sadness at all the edges of things, I laid my forehead against the cold glass and watched the town slide past. The driver took an odd turn I didn’t recognize, and I was about to bark at him for trying to run up the fare (which would have been stupid; no Hiroshima driver has tried that with me once in sixteen years). Before I could embarrass both of us, though, he pulled out by the river and I saw he’d taken a shortcut. The apartment blocks north of the castle were lit up, along with the Rihga Royal Hotel and a few others, and doing their best impression of a city skyline. I smiled. This town. It tries so hard it’ll break your heart.

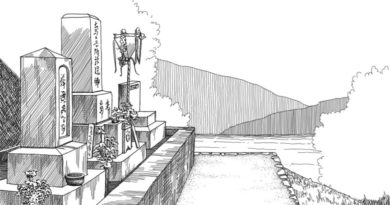

We passed the dark, stooping shapes of the temples in Tera-machi. The rain had lifted. With umbrellas furled, people strolled the riverbank in ones and twos. A streetcar filled with light lumbered over the Aioi Bridge, and then we turned into Peace Park. I caught my first glimpse of this year’s illuminations stretching east along Peace Boulevard. I hate them. My daughters adore them, and they’ll be a cherished childhood memory, along with my own ranting powerlessness (“Who designs this crap? What’s the goddamned theme, anyway?”) to relax and enjoy them. I hope I’m remembered fondly.

The taxi moved past the hospital where my youngest was born. Past the elementary school attended first by my wife, then by our girls. Past the convenience store where my oldest daughter shoplifted her first candy at two and offered to share it with me. Left at the light. Right along the river.

Home.