Bird’s Eye

Years ago, visiting Miyajima, my brother and I leaned against the heavy pillars of the Thousand Mat Hall, furtively sharing a paper sack of chocolate-filled maple leaf cakes and taking in the view.

From the torii gate in the sea below us, the eye traveled up, first to the shrine, then lifting to Daishoin temple sheltered under the forested flanks of Mount Misen. My brother gave a wheezing, happy fat man’s sigh and said, “Levels.”

For a country so mountainous, Japan can do an excellent impression of Denmark. The population centers are mostly flat, even artificially so, as with the reclaimed tidelands where my own house stands. Large towns are linked by excellent roads and rail, neatly obviating the difficulties that once attended long overland journeys. The mountains are always there, usually within sight, but on a tour of the standard sights (Mt. Fuji and a few others aside) they can remain a backdrop, a few moments of darkness as the train hurtles through another tunnel On a trip to Tokyo with my daughter, we waited seventy minutes to ride the elevator to the observatory of the new Skytree. A clear day would have shown us Fuji in the distance, but that day the city itself stretched to the horizon in every direction. If there was a hill out there anywhere, it was hiding.

Mostly, this is fine. I’ve never complained that my bicycle ride to work deviates from the flat only twice, as I cross bridges. But the countryside, which in Hiroshima prefecture means the mountains, shows another side of Japan. I hesitate to say another, older side of Japan, because people have always preferred coastal plains and broad intermontane valleys. In Japan, the obvious reason is rice.

If ripe goat’s-milk cheeses had ever been a staple, there might be more photogenic alpine villages clinging to the heights. Instead, rice fields bordered by mixed-use satoyama, marking the boundary between settlement and forested uplands, are nearly universal in the countryside.

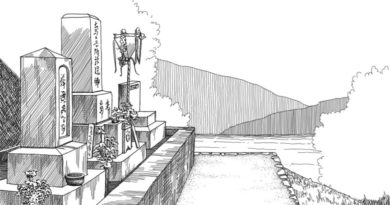

I love to take visitors into the mountains. Even without a car, a bus or train will quickly carry you into valleys where, as my brother noticed years ago, Japan becomes a staircase country of changing levels, all verticals and wheeling shadows. Waterways carve steep notches, and houses cluster around terraced fields beneath the slopes. Climbing out of one valley to plunge into the next, smaller roads break left and right, narrow tracks vaulting upward into the gloom beneath the trees. The leaf-strewn stone steps of old shrines rise toward wedges of blue sky.

Religious structures, enforcing distinctions of high and low, make excellent use of levels. Think of the shrine’s sanctum, perched atop pillars beyond the main hall, or pilgrims leaning over the rails of the great veranda at Kyoto’s Kiyomizu temple. One of my favorite places in Miyajima is an airy room at the top of a steep, turning flight of stairs in Daishoin’s Maniden Hall. By one historical count, as many as 43 peaks on Honshu were once considered sacred. Ascetics of the old mountain faith, a tangle of nearly every religious impulse that ever troubled Japan, secluded themselves among the peaks to seek enlightenment through trials of brute endurance. Some still do.

You wonder, though, how often they broke off from reciting sutras or casting strange spells beneath frigid, threading waterfalls to admire the view. Scenically, Japan does benefit from a bit of elevation. The Seto Inland Sea is lovely from the water, but from the summit of Mt. Kyougoya above Hatsukaichi even the industrialized stretch of coast from Ootake to Kure becomes picturesque. The islands are another wonderful study in levels, as you wind from one bridge to the next past steep citrus orchards where toy-like monorails ferry cartloads of luminous oranges along the slopes.

I suppose I ought to draw some labored metaphor about the ups and downs of life here, the much-discussed vicissitudes of the outsider. I’d rather not. I’d rather leave you with the image of me standing in pink, fresh-scrubbed majesty at the edge of a hot bath high on a hillside on Osakikamijima. Night has fallen on the Inland Sea and fat, island-grown lemons are knocking

winsomely against my thighs. Perhaps you are with me. Perhaps we have a sack of cakes to share, and nothing to say that can’t wait. Below, the sea stretches away black but for patches of light reflected from distant villages and the lamps of fishing boats. Islands rear dark against the sky, like bathers themselves, and there is a trace of smoke on the wind. This will be what you remember. Never neglect the view.