Hiroshima Ground Zero: Memory, Loss, and Legacy

Considering the historical significance of what it marks, the location of the Hiroshima Ground Zero Memorial isn’t at all obvious. The simple plaque on the sidewalk of a narrow street away from the trams that clatter through Hiroshima’s city center can be easily missed.

Many who visit Hiroshima assume that the reason much of the now iconic symbol of the world’s first A-bomb attack, the former Prefectural Trade Exhibition Hall that is now known as the Hiroshima A-bomb Dome, remained intact is that the bomb released in the sky above Hiroshima on August 6, 1945, exploded directly above the building.

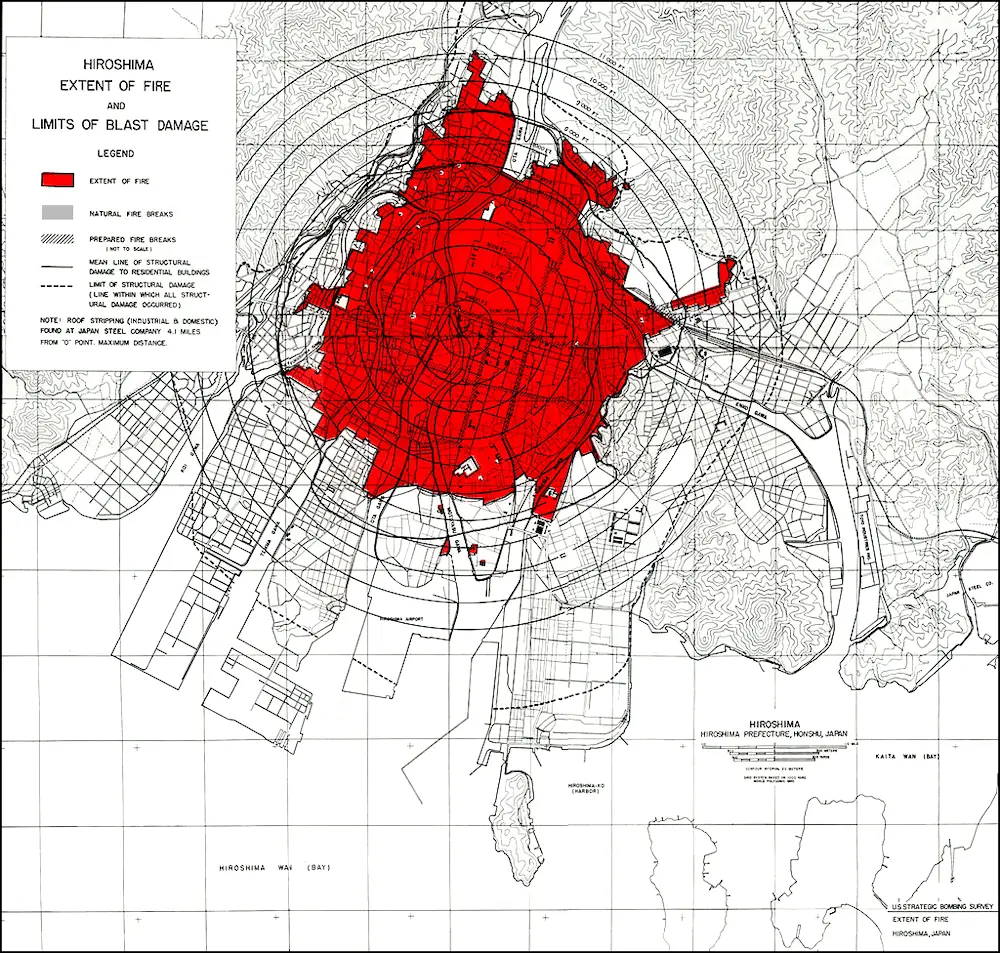

While the target that pilots of the Enola Gay were aiming for was the easily-identifiable T-shaped bridge just across a narrow stretch of river from the A-bomb Dome, the bomb actually exploded 300 meters from its target, 160 meters southeast of the A-bomb Dome.

It was in fact the Shima Hospital that was directly below the A-bomb when it exploded. The hospital was completely destroyed, killing all 81 doctors, nurses, staff, patients, and visitors inside at the time. The hospital in front of which Ground Zero Memorial stands is still run by the same family 80 years after the tragic event.

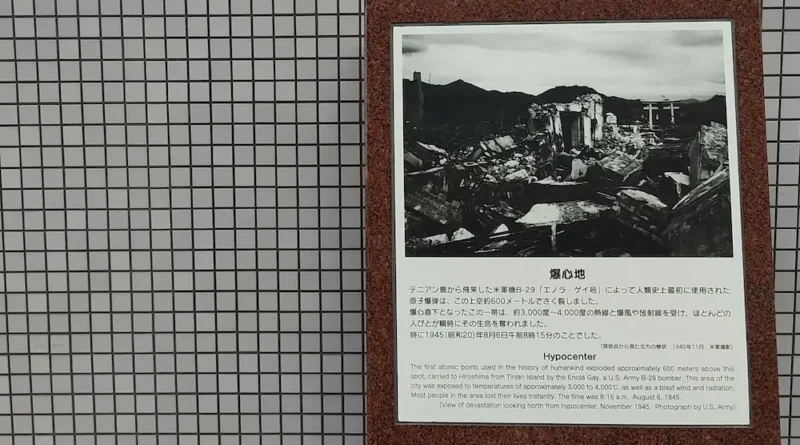

Hiroshima Hypocenter: Ground Zero by another name

While what is termed the baku-shin-chi [爆心地] in Japanese is widely described as Ground Zero, the English term used in official documentation is Hypocenter. The bombs used to attack Hiroshima and Nagasaki were exploded in the air, and the Hypocenter refers to the area directly below the explosion. In Hiroshima, you are more likely to see the term hypocenter in museums and at A-bomb related sites.

Is there a Hiroshima bomb crater?

Perhaps because the term Ground Zero is so closely linked to the site of the 911 terror attacks on the World Trade center in New York, it isn’t uncommon for visitors to Hiroshima to ask whether there is a Hiroshima crater.

The answer is no. As the Hiroshima bomb detonated at a height of 580 meters a above the ground, there was no bomb crater.

A state-of-the-art medical institution with a conscience

Kaoru Shima graduated from medical school in Osaka in 1924 and studied in Europe and the United States before opening the hospital that bore his name in 1933. In his memoirs, he wrote that he modeled the hospital based on what he had seen at the hospital, which would become the Mayo Clinic, creating a system allowing people of all incomes to receive treatment.

Shima’s time in the United States also influenced the design of his hospital. The prewar Saiku-machi neighborhood was known for its Western-style buildings, the prime of which was the Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall (now the A-Bomb Dome). The Shima Hospital, which covered an area of around 1,300 square meters, also had a striking modern design modeled after American hospitals.

It was a two-story brick building with impressive round pillars and circular windows on both sides of the entrance. It is said to have been equipped with the best medical equipment of the time and could accommodate 50 patients, including some Western-style rooms, which were rare then, and rooms for people on low incomes.

Dr Shima also seems to have had a playful side. He kept 5 or 6 monkeys in an enclosure in the hospital courtyard. Perhaps it was to give his patients an entertaining diversion, but people from around the neighborhood would often pop in to see them, too. In this article, you can see a collection of photos taken at the hospital before the bombing. They include one of a man in a white coat feeding the monkeys and one of the mangled monkey enclosure taken a few months after the bombing.

Death and Destruction at the heart of the A-bombing

Dr Shima was proud of his hospital’s study walls, which were more than a meter thick and strong enough to withstand air raids. However, they proved no match for the A-bomb blast, which reduced the building to ruins, with only part of the entrance area surviving.

In a stroke of fate, Dr Shima and one of his nurses had left Hiroshima to visit a patient in the countryside the day before the bombing. They returned when they heard news that something terrible had happened in the city. One can only imagine how they must have felt when they reached the site of what was their hospital. The ruins were radiating heat, and the smell of death filled the air. In his memoirs, published posthumously, Shima recalled that all his nurses were live-in staff, and the hospital had been almost at capacity, with some patients accompanied by family members who prepared their meals.

“There was only one charred body near the gatepost at the entrance, and I knew it was the head nurse, Miyamoto-san, from her gold teeth. I think everyone else had been crushed under the remains.”

Dr Shima and his nurse moved to Fukuromachi Elementary School to provide relief to the people being brought there for treatment while trying to search for staff and patients. He writes how he would tell bereaved families to take home a handful of soil in place of bones that could not be identified.

Rebuilding on Ground Zero

Dr Shima’s children had been evacuated from Hiroshima before the bombing, but his sister and her husband, who ran a nearby pediatric hospital, perished in the bombing. He took in one of their children and in 1948, he started over at Ground Zero. Shima wrote that many bones were uncovered while building a new wooden clinic on the ruined site.

It is reported that Dr. Shima rarely talked about his experiences of the bombing in public, but his daughter-in-law has spoken of his sense of guilt for, as he saw it, failing in his duty as a doctor and member of the Civil Defense Corps by not being at his hospital on that day.

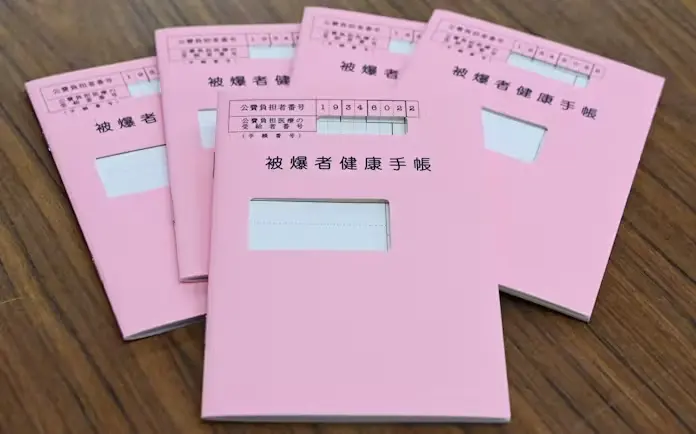

Despite being hampered by information concerning A-bomb d being tightly controlled during the U.S. Occupation, Dr Shima continued to advocate for health provision for A-bomb survivors and was a contributor to the eventual passing of the A-bomb Survivors Medical Treatment Law in 1957.

Two years before Dr Shima passed away in 1977 at the age of 79, he donated six tiles that had been exposed to the atomic bomb at Ground Zero, to the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum —some of the last remnants of that terrible day that had been in his care for almost 30 years.

The leagcy of Dr Shima lives on

Dr Shima’s son took over the clinic after his father’s death, and his grandson continues to provide medical care at Hiroshima Ground Zero to this day.

The modest plaque marking Hiroshima’s Ground Zero stands in quiet contrast to the enormity of what happened here. It offers no grand monument, no dramatic fanfare—just a solemn reminder of the lives lost, the resilience of those who remained, and the quiet determination of a family who rebuilt from ashes. As visitors pass by the Shima Clinic, often unaware of the weight the ground beneath their feet carries, they walk over where history and humanity converge—where healing continues, in the heart of where unimaginable destruction once began.