In Memoriam: Mac

September 2016

This past August, Hiroshima lost a singular and much-loved native son. Masanori Kono, or Mac, was the owner of the legendary MAC Bar.

I met Mac on my second night in Japan. My brother brought me to the bar, gleefully rubbing his hands as we climbed the stairs to the door. I pushed it open, and the music, smoke and sheer energy of the place rocked me back on my heels.

I was greeted by a smiling woman who introduced herself as Yuri. Later that night I met Mac himself and then Boku, the third, irreplaceable leg on which the whole wonderful, improbable mess rested. Boku had built the bar, the stools, and the folding steel racks that housed a vast collection of CDs. The beer was kept below the bar, and a meagre collection of mostly dusty bottles glinted from the shadows at floor level. It was clear that, however much booze was consumed, the bar was about the music. The beer was fuel for the dance, and the dance lasted until you pushed the door open to find yourself blinking in the broad daylight of morning.

The bar had several faces. One appeared late on weekend nights, when dance tunes shook the walls. Mac had usually fled by then, leaving the bar in the hands of Yuri, Boku and anyone else helping out that night. A regular feature of the place was the succession of customers who ended up, by chance or design, functioning as staff.

Another Mac Bar showed itself earlier in the evening, especially in the first few hours after opening on weekdays at 6pm. Mac would often be alone, just setting up, and he’d nod as you came in and rummage under the bar for the night’s first beer. Our tastes in music were similar enough that, even if he wasn’t yet ready for human contact, he could dig out some forgotten Lubbock guitarist’s demo and we’d listen in rapt, companionable silence. Once he knew you, he might pester you about your Japanese, try to teach you Go or Shogi, or drag you off to some fantastic little place you’d never have found alone.

In those early hours, longtime Japanese regulars drifted in and out, often bearing gifts of food or flowers. It was possible to have a quiet chat, working your way toward the bottom of one of the enormous whiskies Yuri and Boku poured, as if there were no other way to drink Scotch than by the quart. Before the crowds arrived, you could also sample the full range of that wall of CDs. Yuri would ask, “What do you want to hear?” One night in a smartass mood, I said “Play me ‘Tammy’” Yuri moved the stepladder a yard to the left, bounced up to the second rung and plucked a single CD from among thousands. A moment later the young Debbie Reynolds’ voice swelled from the big speakers. Magic.

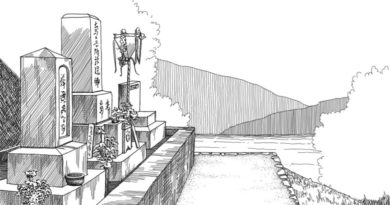

The bar’s first location is remembered fondly by people worldwide. Before cellphones, when even a landline might cost 80,000 yen, Mac offered a central meeting point. You’d scramble up 4 flights of stairs, avoiding the idea of coming down again. Mac was on the top floor, the only business still operating in the building, and the space was tiny. Still, it filled up every night but Sunday until 1am (unless you were lucky enough to be part of a lock-in), sometimes spilling up onto the roof in the early days. Sometime in the 80s, Mac’s customers bought him a CD player. After initial skepticism, the thing stayed. This meant, among other things, a shift from playing albums to song requests. Before the CDs, there was an equally impressive collection of vinyl. Mac would invite you to lob a dart into the stacks to choose the next selection. One night someone leaned the tables against the wall to make a small dance floor, and things changed forever.

Together Mac, Yuri and Boku provided not just a bar, but the core of Hiroshima’s international community. There were more official attempts to foster exchange elsewhere, but Mac was where it happened. The true and wholly unauthorized heart of the city’s international life beat in time with whatever played on the turntable in that smoky upstairs room. People from every corner of Japan, from all points of the globe, came together. Along with English teachers, Estonian pro-wrestlers, Belgian college students, Brazilian soccer coaches and touring musicians, Mac’s deep and impossibly widespread roots in the city brought in a cross section of Hiroshima that included bankers and counterculture dropouts, office ladies and gangsters, carpenters and classical musicians. And they danced.

Over the years Mac and Yuri did a thousand kindnesses for non-Japanese in Hiroshima. They helped finance car purchases, wheeled gift barrels of sake into weddings, intervened with yakuza when things turned ugly at 4am, and arranged a funeral or two for people whose lives came to an end here. There was a warmth and a glad, uncomplicated welcome that met you every time you pushed open that door. Years after I stopped going as often, it felt like coming home. Even when the place was so packed you couldn’t reach the bar, Yuri would spot me and, harried as she was, that famous smile would break out. If it was quieter, a favorite song would be playing within minutes of my sitting down.

I miss Mac. I can only imagine how he is missed by others. I miss the way he’d lunge across the bar, laughing at his own joke, or cock his head to listen intently to some half-assed point you were trying to make. Miss the exultant moods that made him seem possessed. The spirit of the bar is portable and indomitable. It has inhabited thousands of people who, perhaps without any knowledge of one another, carry that connection with them through their lives. But we won’t see its like again. Thank you Mac, Yuri and Boku, for all of it.