Well, that’s over. For now.

A pleasant new development: our 12-year-old daughter is suddenly around a lot more. For two and a half years, she vanished down the rabbit hole of the Japanese entrance exams process. The drama attending these examinations is as much a part of Japanese spring as blue sheets beneath cherry trees, but I’m still asking myself if it was worth it.

My daughters are growing up in one place. One house, by one river. I didn’t. My schooling took me through American public schools, an international school in the Middle East and a boarding school outside Aspen, Colorado during the cocaine boom years. All of these, with varying clarity, colored my thoughts about school for our girls. Knowing our daughters would grow up here, I chose early not to foist an identity on them. They’d speak and read English and know something about my country, but otherwise I’d get out of the way and let them be Japanese. I have former British and American classmates who haven’t seen Saudi Arabia since 1983 and still, in the last gasp of their forties, spend their days wondering aloud where they’re from, posting links to videos with wistful titles like “Where’s Home?” Many of the Arab students fared worse. I know more than a few people, from different backgrounds, who arrived at adulthood speaking two or more languages but without full native ownership of any. Of course every place is different, as is every child. And maybe I’m kidding myself about sparing my daughter’s anything.

On the other hand, for a long time and to some extent even now, the Japanese cram school system seemed like one of the most unambiguously bad ideas ever floated. A childhood should be conducted outdoors, roaming the woods and risking life and limb on a dare. The emphasis on rote learning also rankled, for reasons too frequently voiced to need mention here.

Except that there are no woods near our house, and my daughter doesn’t like poking beneath stream banks for poisonous snakes or setting things on fire, more’s the pity. As for the things cram schools teach, historical periods, major figures, performance of certain arithmetic functions or writing advanced kanji characters, there’s a great deal to be said for simply sitting down and learning it. You can come along and sift in the finer-grained material later.

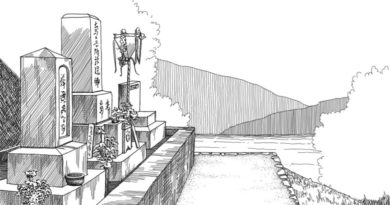

More importantly, my wife (and her friends, and many of my co-workers) speak about cram school with obvious nostalgia. For them it was hardly the unalloyed horror I imagined. It’s expensive and time consuming, and I agree with arguments that it can be socially divisive, that it places excessive pressure on some students. But here were people talking fondly about special exam season snacks, with coffee beans for a late-night edge and names playing on the Japanese words for “pass” or “win.” They reminisced about days when results arrived by telegram, simply announcing sakura saku or sakura chiru. They formed lasting relationships in cram school, and learned lessons in discipline, competition and organization that still elude me.

Wasn’t this, in part, precisely the Japanese childhood I promised to let our girls have? There were other concerns, some more practical than others. Many neighborhoods have excellent public junior high schools. We’re less lucky in that regard and, at any rate, it would only mean postponing things. Weighing any misgivings against my wife’s experience, my regard for her intelligence and judgment (formed in Japanese schools) and what it would mean to keep our daughter out of cram school, I folded like a cheap suit. Just stood to one side biting my fingernails, watching, which is where every parent ends up anyway.

And the girl did very well. Sat at her desk and put in her hours. Three weeks ago, when she learned she’d been accepted to the school she’d set her heart on, I was treated to a shout of exhilarated triumph unlike any noise I’ve ever heard her make. Her mother just wept and laughed. It’s a good school. She’ll enjoy the next six years, and she’s earned them.

America doesn’t offer 12-year-olds many rites of passage any more. The lightness and assurance I see in my daughter these last few weeks suggest that she’s been through something I don’t entirely understand. Every family has different circumstances, different sets of expectations. I want to emphasize that I’m not advocating for anything in writing this. I’ll never know if we made the best set of choices we could have. I’m just enormously relieved that it worked out the way it did. And, already, coiling in knots at the prospect of doing it all again in a few years with our second child.