Lights Out [The Japan Times]

Police use outdated dancing law to stub out nightlife

It’s a lively Saturday night in the heart of Hiroshima’s Nagarekawa district, and some 100 police officers, riot police, immigration officials and U.S. agents gather for a joint operation to bring an end to a licensing infringement of the Public Morals Law.

At a time when Japan has been under fire for its record on human trafficking and organized prostitution, this might be a welcome action in this, Chugoku’s largest nightlife area. Amid the 4,500 bars that are jammed into this one small area, pink salons, fashion clubs, soaplands and hostess bars have always been thick on the ground.

Tonight, however, the morality in question has little to do with the erotic industry. The bar the authorities have set their sights on, El Barco, is well known only for its dancing.

From watching the CCTV footage now posted on YouTube, the operation resembles a minor invasion. Scores of officials cram themselves into the small stairwell in anticipation of the assault on a bar that is one of the very few in the International City of Peace and Culture™ whose staff and clientele is made up of members from all resident nationalities.

“The way the police entered my bar reminded me of some of the darkest days of Latin-American history,” says El Barco owner Richard Nishiyama, a Peruvian. “They came in, in an abusive way, screaming, yelling and pushing our customers into the bar so that no one could leave — as if they were animals or hostages of the police.”

All foreign customers were penned into the corner at the back of the club, while the Japanese customers were separated and allowed to leave. “They checked all of them, one by one, and only when they were sure that there were no problems with their documents did they lead them to the street and let them go — like they were letting animals out of their cages,” says one eyewitness.

Hiroshima’s Prefectural Police have since stated that “in no way was this action based on ethnic discrimination because the persons involved are from Peru.” The fact that the raid happened the day before the trial was due to start of convicted Peruvian child-murderer Jose Manuel Torres Yagi, didn’t escape the notice of Hiroshima residents.

For Amnesty International’s Shinji Noma, this and consecutive raids are violations of the U.N. International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination that Japan signed in 1995. Currently circulating a petition to ask the authorities to put a stop to such actions, he is one of a number of members from various NPOs who have taken an active interest in the actions.

Nishiyama moved to Japan from Peru 16 years ago. Initially working in the car industry, he and his sisters, Hideko and Yuriko, went on to open a restaurant and several bar-nightclubs, each one a success story of the type of entrepreneurial spirit that has characterized Hiroshima’s turnaround these past few years.

Paul Walsh, the editor of events Web site GetHiroshima.com says: “People like the Nishiyamas have worked incredibly hard over the years in an effort to increase the range of entertainment on offer in our town.”

The Nishiyamas are now part and parcel of life here, with even Mayor Akiba turning out for their restaurant’s anniversary party last year.

On the night of May 14, however, Richard and Hideko Nishiyama were arrested.

The police wouldn’t say why such a logistically demanding multi-department operation was needed to deal with a licensing infringement. They do, however, say that such raids are carried out on the basis of information gathered from undercover reconnaissance work beforehand and that they must prepare for the worst-case scenario.

In the event, only one of the customers was taken into custody. After having his apartment searched by the police, a French customer who had left his alien registration card at home was found to have two passports. He was released once the officials had established his dual-nationality.

For the Nishiyamas, however, the trouble was only beginning.

“They took me, along with my sister and two of our employees, into custody at a police station where, using threats, they tried to force me to sign a Japanese document written by the investigator.” Interrogated until 3 p.m. that afternoon and on subsequent days, Richard held his ground, refusing to sign the pre-prepared statement until someone could translate it for him. “They would use threats like, ‘What will happen to your baby boy if we arrest your wife also? Who will look after him with you both in jail?’ ”

Read Richard Nishiyama’s account of his time in custody here.

Nishiyama’s apartment was meticulously searched, his computer and personal documents confiscated, his life history investigated.

Elsewhere, outrage at the actions quickly took root. Support for the Nishiyamas gathered at an unprecedented pace. By the time they were released 10 days later, some 1200 testimonial letters of support had been submitted from people from all over Japan. Though the case involved foreign residents, the bulk of the campaign was organized through the salsa-dancing Japanese community in Hiroshima. Nishiyama was surprised. “I couldn’t believe it,” he smiles. “But I was in prison, not for anything bad. But for ‘making’ people dance.”

The Nagarekawa district is one of 11 nationwide that last year were designated by the government as in a need of “cleaning up.” The authorities are using a 1948 law to do this. Hiroshima City says it wants “to create a wholesome and charming area where a woman can even feel safe enough to enjoy going out alone.” Dancing is part of the fuuzoku eigyou — or entertainment law — and is only allowed to take place until midnight, or 1 a.m. in certain special areas.

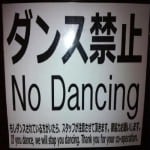

Having been drawn up five decades ago, it still groups dancing with various erotic forms of entertainment. A City Hall official adds, “It’s not dancing that’s illegal. You can dance on the street if you want. Anytime. Just not in a club.”

GetHiroshima’s Paul Walsh is concerned. “Hiroshima was chosen by Lonely Planet (which 10 years ago said that there would be no reason to visit Hiroshima were it not for the A-bomb) as one of their top 200 cities because of its vibrant nightlife.

“The mayor expressed his delight at this in print and online. This vibrant nightlife was built by individuals investing their limited resources in something they are passionate about. In the past month, the prefectural police have effectively stopped that vibrant nightlife and these people are on the verge of bankruptcy.”

One such example is the club Cover. In early September, it and the venue above it, Twisters, were raided by the police, immigration and U.S. officials. Again, Japanese customers were asked to leave while, through a megaphone, “gaijin” were told to stand to one side for questioning. The owners were arrested. Again, these were clubs frequented by the foreign community, and though Cover hosted DJs many nights of the week, it was the foreign run quarterly event “Dirty” that enjoyed the authorities’ attention.

“I’m most angry about one undercover officer. She was dancing for an hour before the raid,” says organizer Mike Waugh. “She seemed really into it.”

Read Dirty organizer, Mike Waugh’s, account of what happened at Cover here.

“Police policy is definitely racist. A Japanese friend who asked the undercover dancer about what was happening, was told that the only reason the police came was to find illegal aliens. The foreign inspectors who came in informed me that it was primarily an immigration issue, but really wouldn’t give any other information.”

Hiroshima’s city office maintains it is not in a position to comment on prefectural police policy or criminal investigations, though an official admits, “It is very unfortunate if Hiroshima is indeed gaining a reputation as being intolerant.”

The police counter that they are not doing anything unlawful or that is not normal police procedure. Procedure dictates that they have to check the ID and status of all foreigners present at such operations, and as long as the campaign to clean up the nighttime entertainment is under way, foreign visitors and residents are advised that they will continue to face such procedures.

The city today is a very different place than the one described by Lonely Planet just six months ago.

* * * * *

It’s October, and what should be a lively Saturday night in Hiroshima. A DJ is playing his set at the normally crowded Sacred Spirits. The dance floor is empty, save for a dozen vacant tables. Posters line the walls with the “No Dancing” message that is visible at regular dance venues all across town. At the bar a few solitary customers sip at their drinks. It’s the heart of the weekend, but lights out for the dance community in Hiroshima.

Elsewhere, U.N. officials from various parts of the world enjoy a drink in the renamed Barcos, and Hiroshima City is preparing for the arrival of the Dalai Lama and Desmond Tutu.

The mayor, so vocal in proclaiming the Spirit of Hiroshima around the world, remains silent on the concerns in his own backyard.

Meanwhile, Richard Nishiyama is getting ready for a trip to the Salsa Congress in Tokyo. “They’re giving me an award,” he laughs, “for going to prison for promoting dance.”

This a repost of an article by Spencer Hazel originally published in THE ZEIT GIST column in The Japan Times on Tuesday, Oct. 31, 2006